Finding freedom in New York State

By Peter Johansen

We walk the lawn that the petite woman, known as “The Moses of Her People,” once walked. We stroll under trees that offered her summer shade. We see photos and artifacts from her storied life, touch the brick wall of her home for good luck, tour the refuge for the aged that she founded. We see the church in which she worshiped and place a pinecone on her tombstone, as countless other pilgrims have done. But mostly we marvel at her courage—fighting snowstorms, changing routes on the fly, facing betrayal by supposed allies, all to lead hundreds of fellow Blacks north to freedom during the brutal days of American slavery.

We’re on a pre-pandemic road trip in northern New York State, visiting sites linked to the famed Underground Railroad, the secret network of escape routes and safe houses that helped liberate nearly 100,000 Black slaves in the first half of the 1800s. All of our stops are fascinating, but none is more significant than this: the Harriet Tubman National Historical Park at Auburn, in the heart of the Finger Lakes.

Tubman’s final homestead—provided by William Seward, Abraham Lincoln’s Secretary of State and a staunch abolitionist—has been open to the public since the 1950s. But it was only in the final days of Barack Obama’s presidency that it won national historic designation. (Tubman’s Maryland birthplace is also a national park, showing just how iconic a figure she remains.)

Tubman was born a slave 200 years ago this year. Her master rented her out as a child tom other plantation owners. Maliciously struck on the head by an iron weight at age 14, Tubman suffered

epileptic seizures, fainting spells and visions for the rest of her life. But that didn’t stop her from escaping north to freedom—living for a while in St. Catharines,Ontario—and then sneaking back south at least 13 times to free others. As a spy, she helped lead a Civil War raid against a Confederate encampment, destroying enemy food and munitions, releasing captives, and nursing the wounded. In later years, she became a leader in women’s suffrage.

In Auburn, an interpretive centre quietly details her story. Once pandemic restrictions lift, visitors may again tour the white clapboard house that Tubman deeded to her church as a home for elderly indigent blacks. Long neglected, it’s now refurbished with artifacts, many from Tubman’s descendants. Among them: a bed with a quilted rag doll, good china atop a lace doily, her treadle-operated sewing machine, a family Bible that the illiterate Tubman couldn’t read, but knew well thanks to a gifted memory.

Tubman died in poverty but has become rich in honours. A Second World War Liberty Ship was named for her. She’s been featured on U.S. postage stamps; a $20 bill is promised. A 2019 feature film depicted her life; Cynthia Erivo’s portrayal of Tubman garnered an Oscar nomination.

Yes, Tubman is famous, but our trip uncovered equally inspiring, if lesser-known, figures too.

One is Slocum Howland, who lived in the hamlet of Sherwood, just a few kilometres from Auburn. He built a general store there in 1837. It remained in family hands until 1942. He was a canny businessman, investing in stocks and land, even selling textiles to the Civil War military. How successful? His three kids each inherited $1 million. But as a Quaker, Howland practised social justice, and his home became one of the state’s most active safe houses for escaped slaves. His holdings included docks on Lake Cayuga, which eased the spiriting of fugitives north to freedom in

Ontario.

The Howland Stone Store Museum, now on the register of National Historic Places, displays abolitionist artifacts, none more prized than a Railroad “ticket” offering safe passage to two brothers from Maryland, whom Howland housed for a spell. Other posters, photos and bric-a-brac supported women’s suffrage, to which the Howlands were also keenly committed. Among the rarest: a piece of birthday cake from the 78th birthday of suffragette leader Susan B. Anthony, baked in 1898. It is, museum volunteer Ann Tobey told us, “beyond mold.”

The store’s second floor displays a “cabinet of curiosities” collected by the well-traveled Howlands, an eclectic jumble that includes a Tunisian cushion made of gazelle skin, a slab of alabaster taken from a temple to Ramses II, and a stone from the valley where David supposedly slew Goliath.

Howland wasn’t the only businessman fighting slavery. Moving east to Mexico, NY, we found the Starr Clark Tin Shop, another museum honouring an important station master, as local abolitionist leaders were called. Starr Clark took over the local general store in 1832 and added tin-smithing to the business. It became the hub of community activity, including lively political discussions.

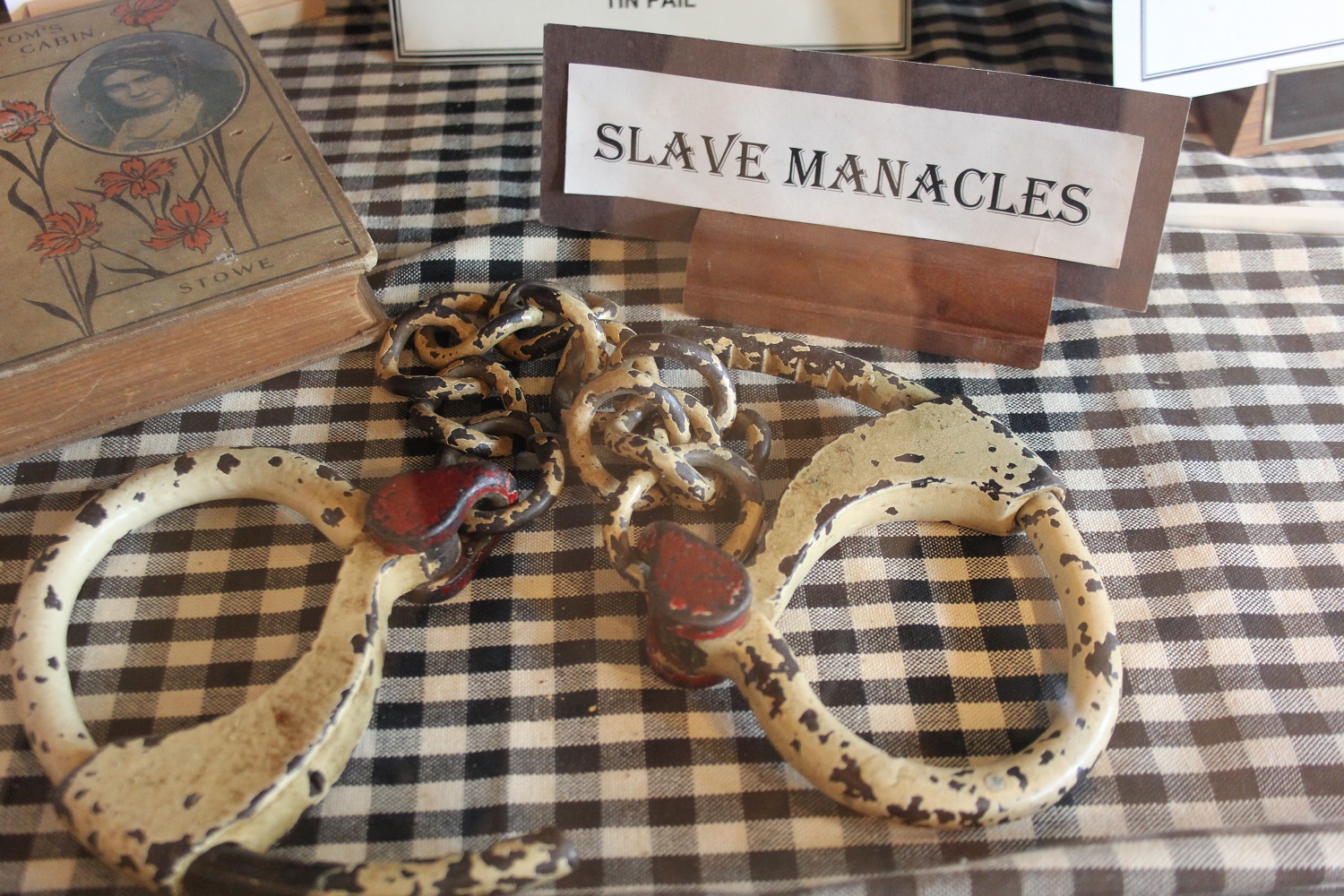

But the store was also the last stop on the Underground Railroad before fugitives reached Oswego and a boat to cross Lake Ontario. In addition to interesting displays of tinware and tin smith tools, we found rare examples of antislavery china that Clark used to feed ex-slaves holed up in his house, quilt patterns that secretly signalled directions for fugitives to follow (black squares indicated an abolitionist house), an 1857 map of Oswego that helped abolitionists identify safe houses, and a model of a wagon used to transport runaway slave William “Jerry” Henry.

Henry had escaped to freedom in Syracuse, NY, where he became a cooper, building salt barrels. But under a law allowing bounty hunters to capture ex-slaves and return them to their former owners, Henry was captured and jailed. Luckily, a convention of abolitionists was meeting in Syracuse and delegates devised an escape plan, likely with the authorities’ cooperation.

Henry was hidden near the jail while police flew off in all directions. He was spirited to the Tin Shop four days later by a sympathetic butcher delivering meat. Eventually, Henry made it to Kingston, Ontario, where he worked as a chair maker. Among the museum’s most prized possessions is one of the chairs he crafted.

Alas, Henry lived freely in Canada for only two years before he died. It’s believed he’s buried in Kingston’s Cataraqui Cemetery, in an unmarked grave. Cemetery officials have no record of him. Unlike that of Harriet Tubman, not every Underground Railroad story ends in fame.

Want to Go?

Check museum websites for operating hours and COVID-related restrictions: harriettubmanhome.com; howlandstonestore.org; mexiconyhistoricalsociety.com.

Other Underground Railroad sites in New York’s Cayuga and Oswego counties include the Seward House Museum in Auburn and several homes and businesses associated with white abolitionists and ex-slaves alike in

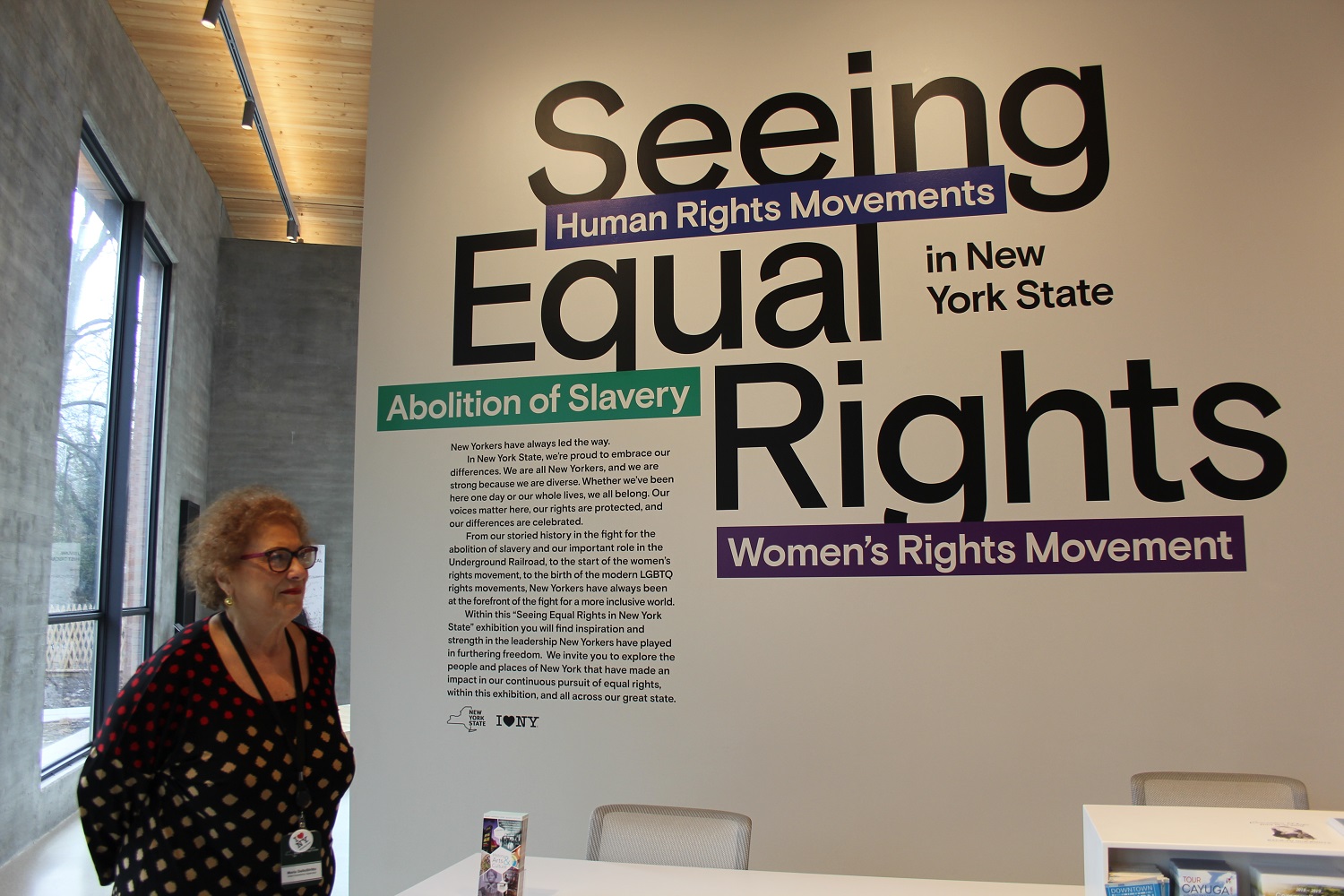

Oswego. To appreciate the abolitionist movement within the context of U.S. civil rights generally, visit the New York State Equal Rights Heritage Center in Auburn.

The area also boasts dozens of wineries and craft breweries, robust nature adventures (from hiking to birding), professional theatre, and other historic sites. Information: tourcayuga.com; visitoswegocounty.com.

In Auburn, we stayed at tranquil Springside Inn overlooking Owasco Lake, which has its own Underground Railroad story; ask owner Sean Lattimore for details. Our Oswego lodging was the comfortable Clarion Hotel on the riverfront.

Hungry? In Auburn, try breakfast at New Hope Mills, dinner at Next Chapter Brewpub, and lunch at Fargo Bar and Grill in neighbouring Aurora. In the Oswego area, we liked the fresh salads at Mill House Market in Pulaski and the innovative dinner menu at Oswego’s Bistro 197.

Well done!

Peter’s November-December 2020 “Curious Trekker” column earned him the Gold Medal for Health and Wellness Travel in the annual award competition of the North American Travel Journalists Association. Given that winners include heavyweights like En Route Magazine and the New York Times, this is a impressive recognition for Peter, and we’re happy to ride on his coattails. Details can be found here https://www.natja.org/awards/annual-competition/2021-awards-winners/