By Rose Simpson

The late actor Matthew Perry once believed that all his troubles would go away if only he became famous.

He remembered at 24 kneeling and praying, hoping to make his dream come true.

“I prayed to God to make me famous,” he told the CBC’s Tom Power. “I told God he could do anything to me after that.”

Three weeks later, he got the role of Chandler Bing on the hit NBC series Friends, which made him more than $100 million over its 10-year run. He had houses, famous girlfriends, and movie roles.

“I liked it for about six months,” he recalled. “It didn’t fix my problems. It didn’t solve anything. I still wanted to drink every day.”

Matthew’s path to addiction began in Ottawa when he was 14 and had his first taste of alcohol. Sitting in his backyard with childhood friends, he downed a bottle of Andres’ Baby Duck.

“I was lying in the grass,” he wrote in his memoir, Friends, Lovers and the Big Terrible Thing. “Something happened to me. For the first time in my life, nothing bothered me. The world made sense; it wasn’t bent and crazy.”

That first sip led to a 30-year addiction to alcohol, prescription medication and illegal drugs. All he wanted, after fame, was to chase that feeling of bliss. He lived his life through a revolving door of sober houses and rehab facilities, and his use of opioids led to a life-threatening bowel rupture.

As a last ditch effort to stay sober, Matthew decided to pen a memoir in 2021 to help others on their path to sobriety.

“The good thing about me is that I will help people if they ask,” he wrote. “That’s the ticket for me, helping people whether it’s on a large scale or just one guy.”

Sadly, Matthew lost his battle with addiction in 2023 after an overdose of ketamine, a drug ironically meant to help with addiction. He was found unresponsive in his hot tub.

“I didn’t want to have this problem,” Matthew told Tom Power. “It’s so cunning and baffling. If I could just have said no, I wouldn’t have had to go to 9,000 AA meetings. I could just stay home and say no.”

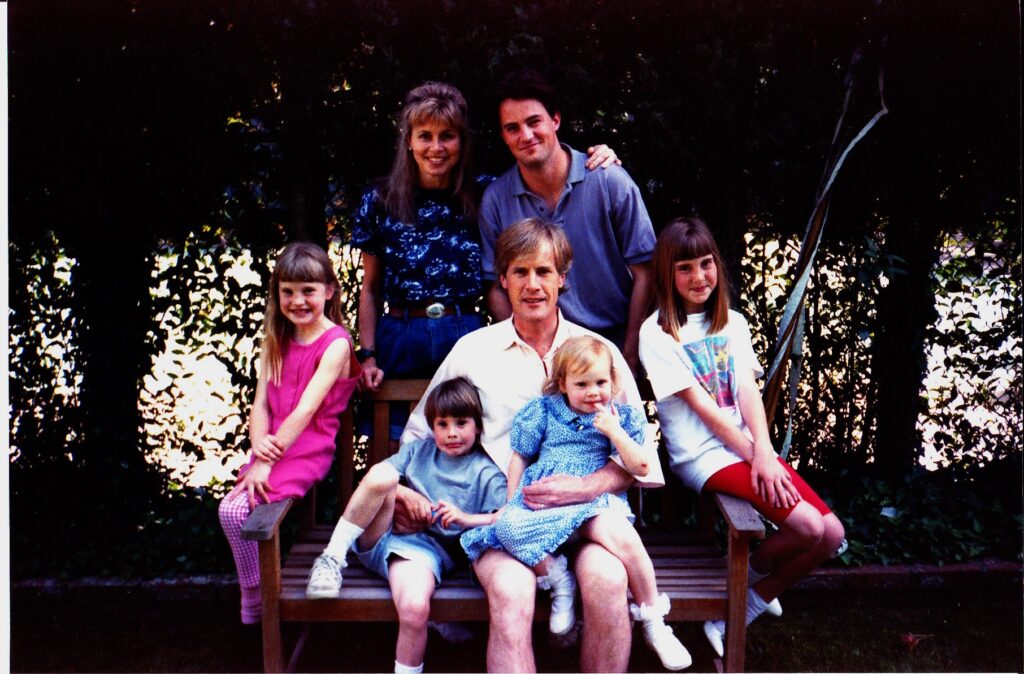

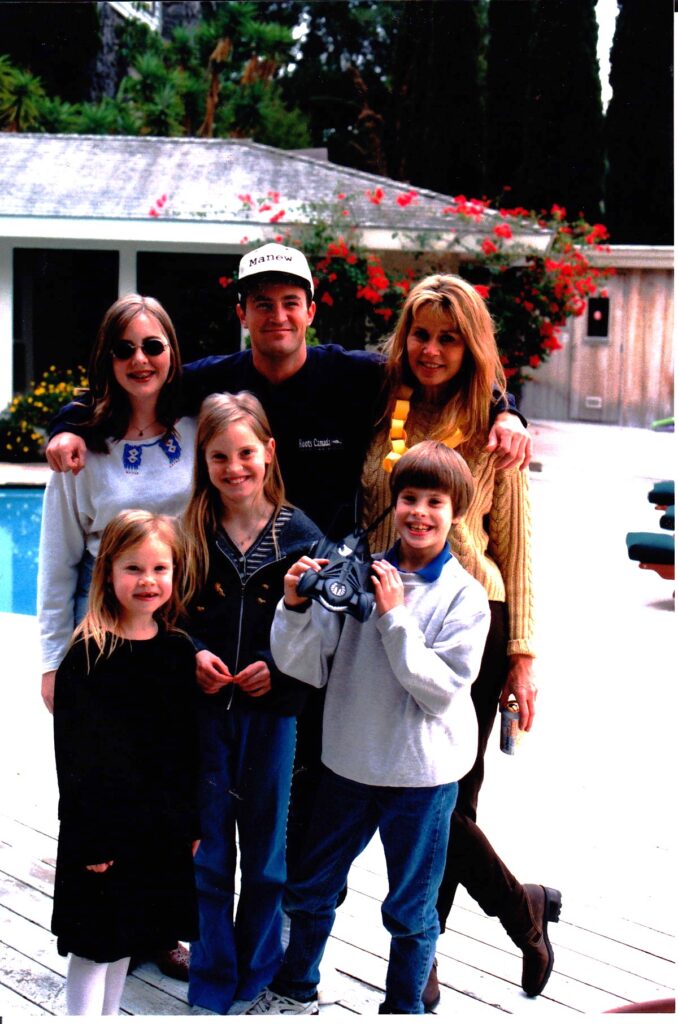

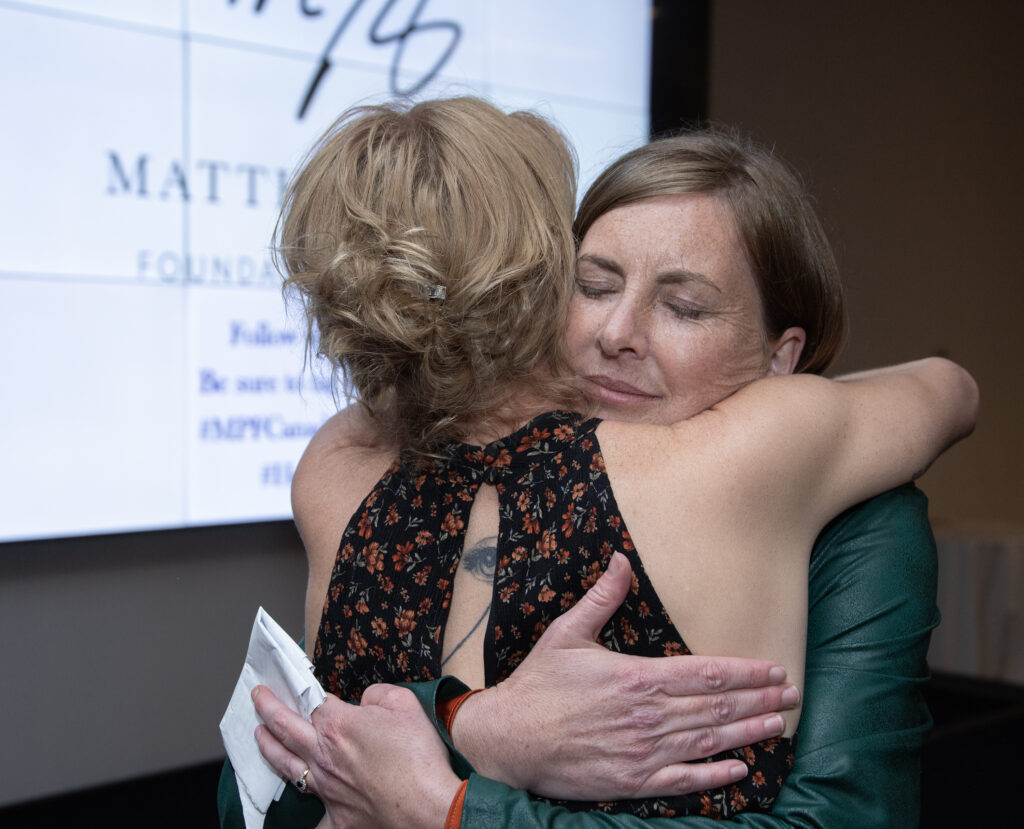

After Matthew’s death, his family wanted to find a way to honour his memory by creating The Matthew Perry Foundation of Canada, which went public in October 2024 on the first anniversary of the star’s death.

It is headed by executive director Caitlin Morrison, Matthew’s sister, and has a board of directors that includes childhood friends and his mother, Suzanne Perry, who was press secretary to Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau in the 1970s. The effort is also supported by Matthew’s famous friends, his siblings and his step-father Keith Morrison, NBC Dateline host and the former anchor of Canada A.M.

Caitlin Morrison believes her brother gave her an assignment.

“I knew very early on I needed to do something after he died,” says Caitlin. “I feel, my whole career, I’ve been in training for this. I just wish it had happened in a different way.”

Her own interest in helping others get sober peaked when Matthew’s staff and manager started a foundation in the United States, following his death. A veteran of the not-for-profit community, Caitlin spoke to experts and realized a more grassroots approach was needed in Canada to effectively help more people more quickly.

“The experts all emphasized the need for post-treatment housing, and job supports, among other things.”

The foundation wanted to ramp up quickly, so it reached out to organizations with long histories in the addiction and mental health space.

“It lets us do more,” she explains. “Those partnerships are key because they give us an overall picture. We can pool our resources, pool our planning, build something that is very much needed and do it more quickly.”

A key priority is to build a Matthew Perry House in Ottawa which will offer housing, counselling and other resources for people coming out of treatment. It will be a transitional space that is scheduled to open its doors in 2027.

“When people walk out of the doors of treatment, we want to grab them by the hands and help them walk down the rest of the road,” she says.

The foundation will soon offer peer support for individuals and their families by connecting families and those suffering from addiction with others in the same situation.

“It will be informal,” she explains. “We’re keeping a data base of people who reach out to us and when we find two people who are close to each other, and have the same kinds of experience, we’re connecting them. This is somebody you can have coffee with, go grocery shopping with. Each one will be a safe person, someone who will pick up the phone at 2 a.m.”

The plan includes a program to train individuals who have successfully completed two years of sobriety to help others avoid post-treatment obstacles. Mentors who complete training and get paired with a mentee will have access to their own mental health supports through MPF Canada. The Foundation is also planning a pilot project that will identify one Canadian “small town.” Its staff will reach out to local organizations in that town and offer housing, counselling and career support for everyone who needs help in their first two years of recovery. The foundation hopes to be able to expand this program across Canada.

“We have a unique opportunity to connect people, to understand what they need, and build our programs on the basis of what people need.”

The Matthew Perry Foundation of Canada is also looking for volunteers and donations.

“If you contact me, I’ll reach out directly to you,” she says. “We are interested in people who want to build something, and others who are willing to share their stories.”

www.matthewperryfoundation.ca.

Waiting for the Shoe to Drop

Rose Simpson talks about her son’s struggle to stay sober.

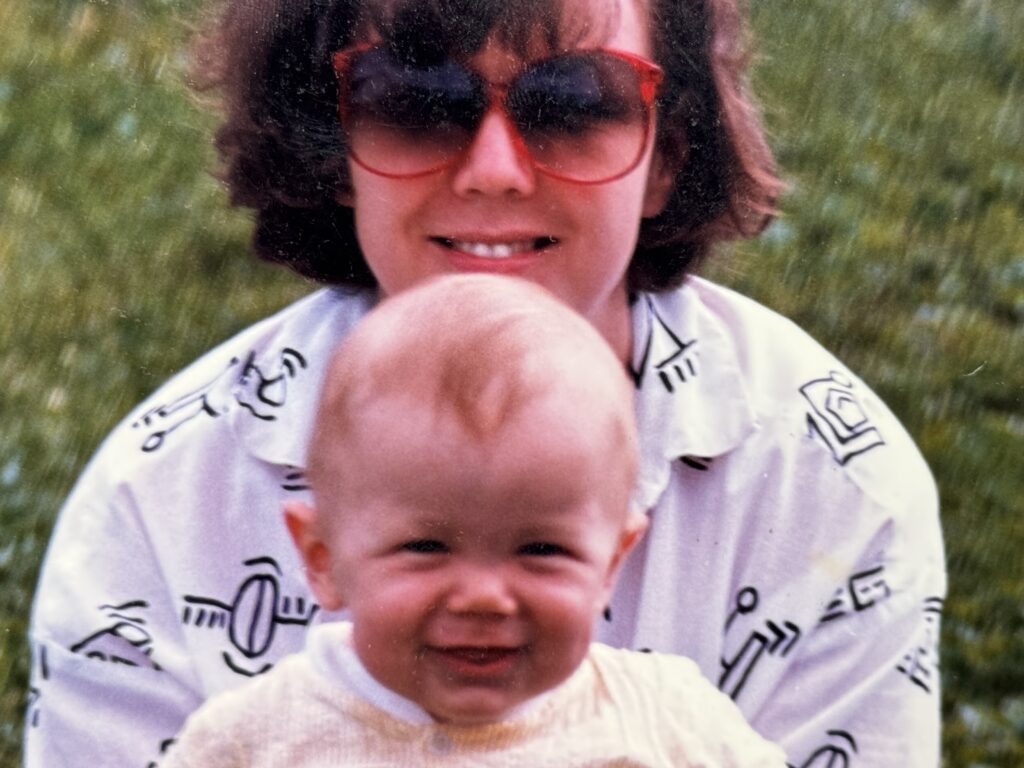

For 20 years, I’ve been afraid to get “the call” from my son.

Nick could go for months without talking to me. Then, the phone would ring and I knew the sky was falling. The sky was always falling in his world, at least.

He’d broken up with a girlfriend. He’d lost his job. He was out of money or out of time.

I loved him dearly, but it was exhausting being his mother.

Mostly, Nick was an unrepentant pothead and chain smoker.

But there was the time when he headed off to Barrie, Ontario, with a friend, and went down a rabbit hole. I sent my husband to get him and I was horrified to see his physical state. His eyes were sunken into their sockets and he was skin and bones. He’d also stopped taking his thyroid medication.

Nick had always been in trouble, whether it was with drugs or alcohol. He tried them all, loved them all. We nearly lost him a few times. He was homeless in his teens, depressed and in active addiction for most of his adult life.

The last time I got “the call,” he told me life was hopeless and he felt suicidal.

I quickly scooped him up and headed to my wonderful family doctor who referred him to a psychiatrist.

This somehow made him feel better, as if someone had finally confirmed what we already knew—that he was in the depth of despair.

The referral took a few weeks, but he seemed better just knowing that he would be seen by professionals.

“How did it go?” I asked him after the psychiatric evaluation. “Are you going in for treatment?”

He shrugged. “They say I’m not bad enough.”

I was shocked. I’d heard those words once before, after a friend of mine sought treatment for alcoholism. Maggie drank day and night. In her 40s she realized that she needed help.

“You’re just not bad enough,” the addiction counsellors told her, and gave her a few pamphlets. A couple of years later, she arrived at the hospital with a swollen belly. The doctors told her she was suffering from cirrhosis of the liver. She was told to go home and get her affairs in order.

I am convinced Maggie would still be with us today if she had been offered treatment and after-care instead of pamphlets. I’m convinced both Maggie and Nick were indeed “bad enough” when they sought help.

As families, we simply can’t out-love addiction. My son’s and my friend’s conditions were too complex to be fixed by attending an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting. They both suffered from a life threatening illness.

Maggie did indeed die from her disease, in spite of best efforts. My son was more fortunate and eventually received treatment for his underlying mental health issues.

He now takes medication for depression and dutifully reports to a therapist every other week. He has managed to get his life back on track. He is in a loving relationship and has a beautiful daughter and newborn son.

He works full time, as a security guard on Parliament Hill, and recently earned a diploma in business/marketing from Algonquin College. He made the Dean’s List. Nick is also a published author, having written more than a dozen books over the past decade. We recently celebrated his 39th birthday. It makes me wonder what he could have achieved over the past 25 years had his illness been identified and treated sooner. I wish the resources offered by the Matthew Perry Foundation of Canada had been available when he was young.

As Matthew Perry so wisely noted, addiction never goes away.

As Nick’s mother, I continue to feel a chill when the phone rings late at night.

Those of us who have witnessed and experienced it understand that addiction is forever.

All we can do is hope the other shoe doesn’t drop.