In retirement, psychiatrist, educator and Holocaust survivor Kati Morrison continues to make a difference, talking to school groups about the Holocaust and racism.

By Iris Winston

“What do you need?”

This is a question that Kati Morrison asks most acquaintances—especially young couples—these days, as she and Bob, her husband of close to 50 years, prepare for the next stage of their lives.

“We have a plan,” she says. “We’re downsizing and intend to move from our four-storey house to independent living in a retirement home next year. We’re both very well now, but we don’t want to wait until we’re not. We live day to day, enjoying our house and trying not to make too big a mess while we’re downsizing.”

Always a pragmatist, Kati, a retired psychiatrist, accepts their upcoming move as a natural part of aging, just as she has accepted and dealt with other curve balls through her life.

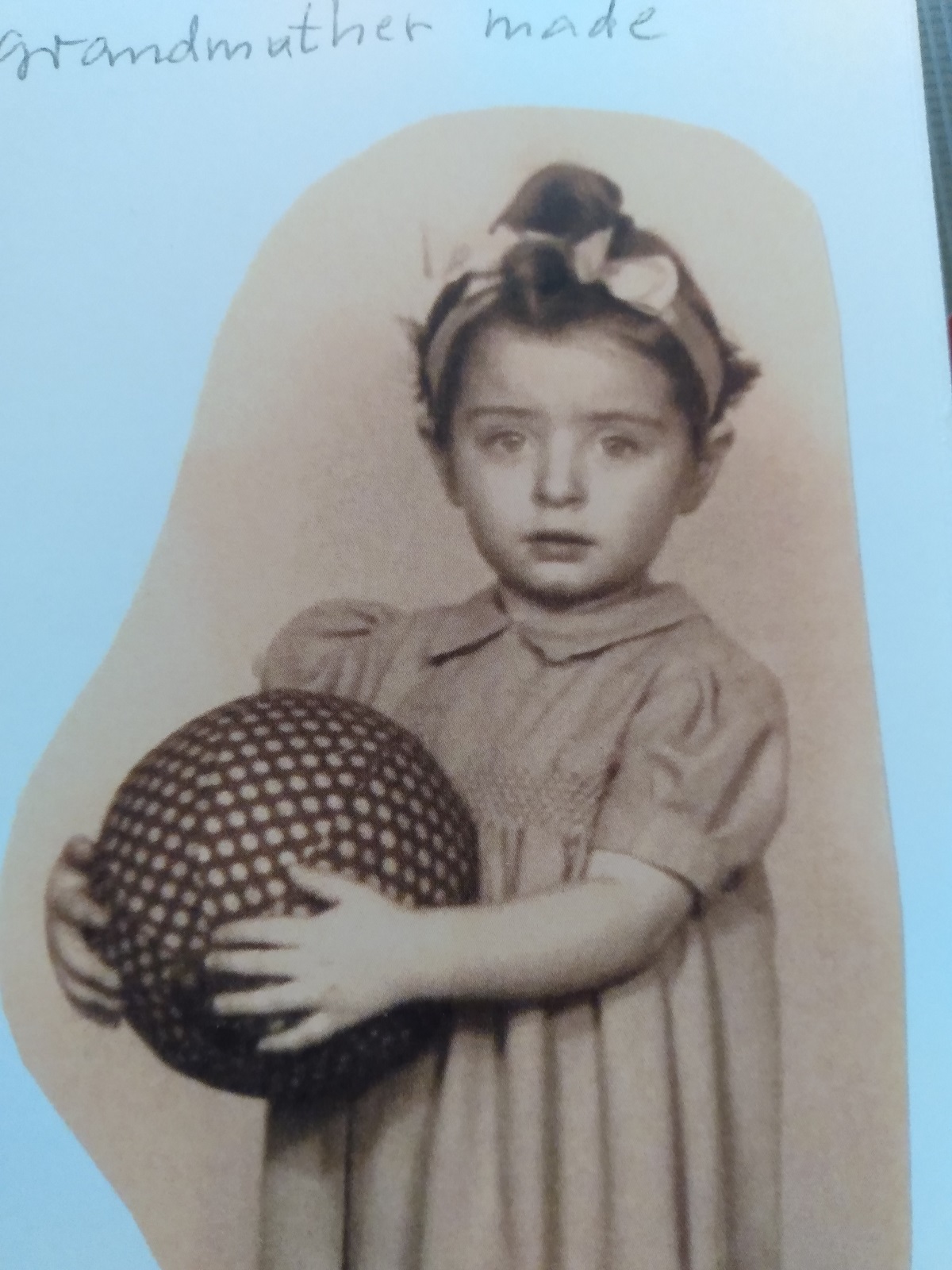

As a young child in Hungary during the Second World War, she lived with her grandmother while her father was forced into slave labour and her mother was incarcerated in a concentration camp.

Hungary allied with Nazi Germany and passed a significant amount of anti-Jewish legislation after 1938. The Communist regime in place after the war was similarly oppressive.

“You didn’t talk about being Jewish because the undercurrent was that being Jewish meant you were going to be killed,” says Kati, “so we had no Jewish traditions growing up. The world was a scary place, but the family was my haven.”

As a Holocaust survivor, she is now sharing many of the experiences that had a direct impact on her and her family.

“Going into schools to talk about the Holocaust and against racism is an important part of my life,” says Kati, who was born in 1940. “I find the teachers’ and students’ interest most rewarding and helping people has always been important to me.”

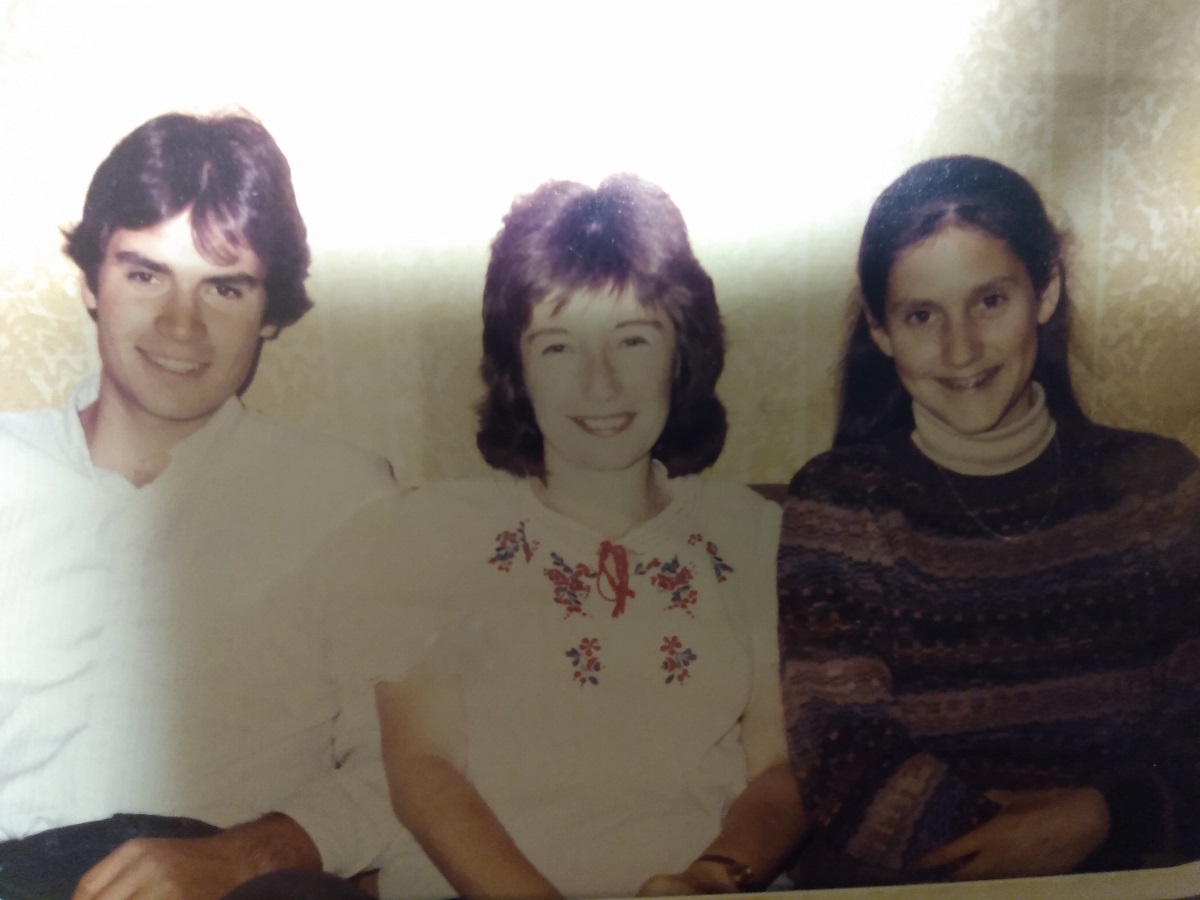

Her two stepchildren are also a very important part of her life. “In fact,” she says, “I don’t think of myself as a stepmother. I’m just a parent.” When Kati immigrated to Canada and married Bob, his daughter was five and his son was eight. “In 1972, when we met, men did not usually get custody of their children,” she explains. “I felt very privileged to be with a man who was such a good father. And the children were delighted when I came to the family.”

However, two of her friends faced problems as stepmothers and came to her for help. The three became a study group and then gave workshops that helped women learn boundaries and to respect their stepchildren’s feelings towards their mothers.

Results of those workshops and a study Kati did of 24 stepmothers were eventually developed into a book, Stepmothers Exploring the Myth, used in social work classes at the college level.

“I was very pleased to be able to help stepmothers this way,” says Kati. “As a child psychiatrist, I had a lot of ideas about children’s needs. … And I was very happy to have a family.” Today, she adds, “I’m a grandmother and I still get the biggest bouquets on Mother’s Day.”

After four decades as a practising psychiatrist and then a teacher and supervisor at the University of Ottawa, Kati needs to stay active in her post-work years. In addition to devoting time to her family and Holocaust education, she’s also enjoying music and poetry.

Where music is concerned, she plays the flute as part of a trio with a banjo player and a fiddler. “The first time we played together was at Crosby Lake where we had a cottage for a number of years, so we call ourselves the Crosby Lake Trio,” she says. “It was totally spontaneous. We still have jam sessions together.”

With regard to poetry, “It just pops out of my head,” says Kati. “I’ve written quite a bit relating to my identity and the Holocaust, a bit about my mother’s decline and loss and most recently quite a bit about aging.”

“Not that I feel old,” she says. “It’s not that I don’t experience changes and have some physical issues, but because of the war and other horrible experiences in life, I feel that aging is a natural thing. …I’m very lucky to have a wonderful partner, a group of good friends and meaning in my life. I try to help and support others, so my life is full.”