by Iris Winston

Starting life in a nation in conflict and almost being killed by a nearby vehicle blowing up are just two reasons John McGarry has spent much of his career trying to bring peace to countries around the world.

Most recently, that dedication has been recognized with the Pearson Peace Medal. The prestigious award is named for former prime minister Lester B. Pearson, who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1957. It honours an “outstanding Canadian who has made significant contributions towards those causes for which Lester B. Pearson is remembered.”

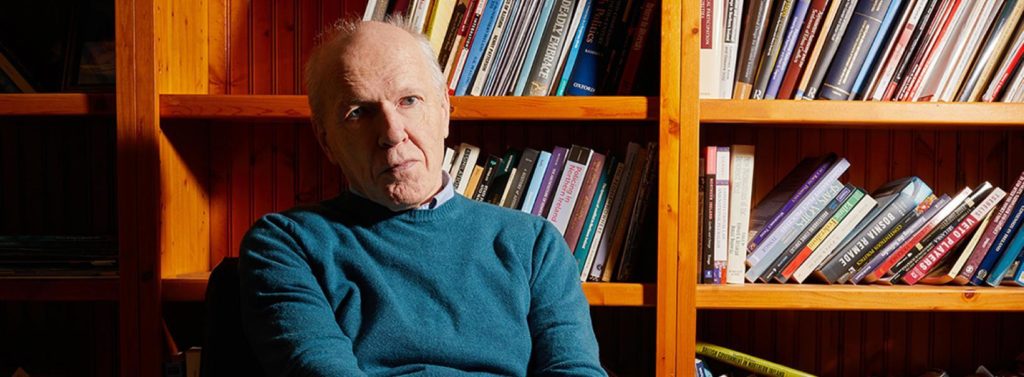

“It’s a great honour to have received this award,” says John, who holds numerous academic honours and who was named an Officer of the Order of Canada in 2016.

“It’s the first award I’ve ever received purely for peace and that’s a pretty important part of what I’ve been working on for the past 30 years.” As he speaks of the place—Northern Ireland—where his longtime commitment to global peace began, he says, “I wasn’t in one of the most dangerous places, but everyone felt the conflict one way or another.”

Some 30,000 people were injured “through the course of the conflict,” notes John, who was born in Belfast and grew up in Ballymena, County Antrim. “Everyone knew someone who had been affected…. I wanted to find out how to deal with it in a way that would build peace because I lived there. My family lived there.”

Eventually, he had a significant influence in helping end The Troubles in Northern Ireland through the 1998 Good Friday Peace Agreement. He has also had a stellar career as a renowned professor in political studies at Queen’s University in Kingston. That continues, as does his work in the field on public policy and the practical aspects of conflict resolution for such organizations as the United Nations (UN).

John’s field work has taken him around the world, most often to Cyprus where he currently serves as lead advisor on power-sharing and governance in UN-backed negotiations. He has also been heavily involved in seeking peaceful resolution to conflicts in Bolivia, Kenya, Moldova, the Philippines and Iraq.

As well as writing about and working towards peace in many places, he has conducted negotiations through the UN in New York. Iraq, for example, was one of the countries for which he worked at a distance, rather than going to the country.

“The person who invited me in 2003 told me I shouldn’t worry about security,” he recalls. “I was to ignore everything I had been told about the problems getting into Baghdad. He said the plane coming into the airport had to make a very steep descent to avoid incoming flak. He also said that when I arrived, there would be three cars, one in front and one behind me. I would be in the middle so I wouldn’t have anything to worry about.”

“But,” he adds, “I’d been told that many people had been killed on the route from the airport, so I thought there was something to worry about. But, even so, I would have gone there, if I hadn’t been working on something else at the time.”

Then and now, it’s a punishing schedule. As a full-time university professor and research chair, he has all the usual academic responsibilities. He has written and co-authored some 25 books and numerous articles for academic journals, as well as contributing to public media. He also has heavy responsibilities as a consultant trying to bring conflicts to satisfactory conclusions via negotiations and mediation.

“And when I’m working at the UN, I have to take time off from my university job,” says John. He was senior advisor on power sharing for the UN from 2008 to 2009 and currently sits on the advisory council of the Centre for the Study of Democracy. “I have two busy jobs and one doesn’t stop while the other is on.”

There is added value in combining his work as an academic and a practitioner, he adds. “You can bring your experience back to the classroom and the students are really interested. And you can also take some of their suggestions back to the field.”

At 66 and with three adult children, John says he is approaching retirement from the university, which will give him more time for his field work.

“I would like to continue playing a role in Cyprus,” he says. “I’m very concerned for the people on that island. I also want to have a role in what’s happening in Ukraine. When the fighting stops—and nothing will happen till it does—we can focus on the kinds of issues I deal with on how to govern a country in a way that respects its communities.”