By Iris Winston and Photos by John Major

Under Water and Beyond Canada’s top Underwater Explorer

Jill Heinerth, lives her passion for adventure.

A new day, a new adventure.This is the way life has been for cave diver Jill Heinerth ever since she started exploring the planet from the inside out.

“I’ve always been a water baby,”says Jill, who was the first person to explore the underwater caves of Antarctica. “We rented a cottage near Haliburton when I was growing up and, according to my mother,I regularly stayed in the water until my lips turned blue.I just loved swimming and I’ve always been inspired by exploration. When I was in kindergarten, I remember being herded into the school library and crowding around a crackling black-and-white television to watch men drive around the surface of the moon.”

“In fact,” adds Jill, who started life in the former Cooksville (now Mississauga, Ontario),“one of my first career aspirations was to be an astronaut. But Canada didn’t have a space program back then and we certainly didn’t have women astronauts at the time.” So, instead of journeying into outer space, she chose to explore inner space and became a pioneering aquanaut. The recipient of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society’s Sir Christopher Ondaatje Medal for Exploration and, currently, the society’s first explorer in residence,she is generally acknowledged as one of the world’s top cave divers. Also known as technical diving, cave diving is extremely dangerous because divers have no direct route to the surface.The only way out is to swim back through the same tiny spaces they entered on the way to the depths.

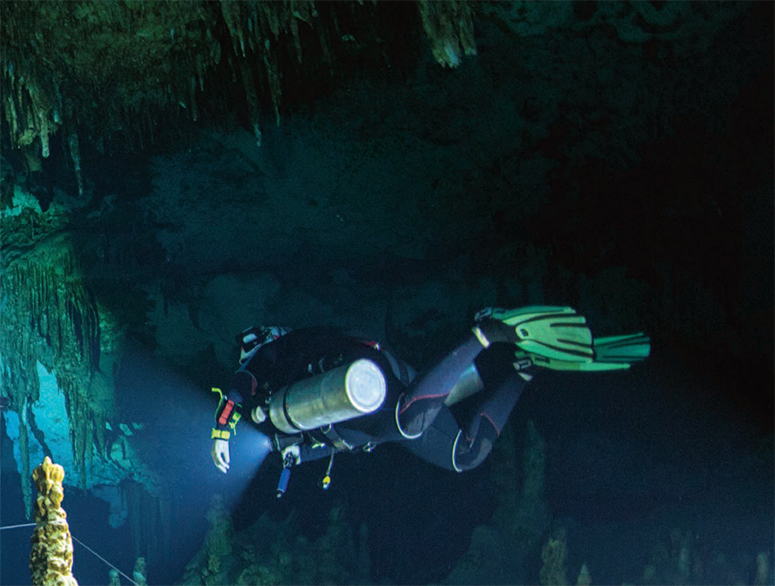

They work in darkness, moving through icy pools filled with stalactites and stalagmites. Cave diving and three-dimensional mapping of underwater cave systems require specialized training and considerable skill. “Technical diving and exploration diving take people beyond the realm of recreation,”Jill explained in a recent interview with The Clymb. “In recreational diving, you can always just abort a dive and swim straight up.In technical diving, we are often in overhead environments like caves and wrecks and under an obligation to decompress our bodies before resurfacing.”

Over the years, Jill has had a number of close calls, including having strong currents pin her inside an iceberg cave in Antarctica and being trapped behind another diver wedged in a minute underwater pathway. To lessen the danger,Jill uses such specialized equipment as rebreathers, which recirculate exhaled breath. (Astronauts use similar equipment for their space walks.) While keenly aware of the risks involved in cave diving, Jill, who has collected numerous honours as an underwater explorer, including the 2011 Wyland Icon Award, continues to “swim through the veins of Mother Earth.”

The Wyland Icon Award is presented annually to luminaries and pioneers of ocean conservation to recognize the achievements of those who have made a positive difference for the underwater world. “If you have the right training, carry appropriate equipment and plan for the worst, you can get yourself out of most problems,” says Jill, a member of theWomen Divers Hall of Fame since 2000.

The Wyland Icon Award is presented annually to luminaries and pioneers of ocean conservation to recognize the achievements of those who have made a positive difference for the underwater world. “If you have the right training, carry appropriate equipment and plan for the worst, you can get yourself out of most problems,” says Jill, a member of theWomen Divers Hall of Fame since 2000.

“I love the sense of being able to go where nobody has ever been before and maybe nobody will ever go again. I think that principle has guided a lot of my decisions in life.I think of myself as incredibly privileged to be able to explore the inside of our planet. It’s almost a spiritual experience for me to be within the lifeblood of the planet in those water resources that nourish everything from agriculture to humanity to industry. To be there at the beginning of the pipe and see where it comes from is an incredible opportunity. Through those adventures exploring the inside of the planet, I’ve recognized that this unusual thing that I do is fascinating enough to people to allow me to tell the story, to talk about my adventures and tell people how important that water resource is to us.

She does this in various ways. As explorer-inresidence, supported by the Garfield Weston Foundation, she has traveled across Canada speaking to small groups and giving workshops on photography and journalism — two other aspects of a multi-faceted exploration diving-plus career that includes being the stunt diver in a James Cameron movie about cave divers trapped underwater. Her presentations to the youngsters she meets offer ideas on unusual career opportunities and the importance of discovery in learning. “It’s an incredible experience working one-on-one with kids,” she says.

“You can show them all the DVDs in the world, but when you talk to them, you can have a real impact on their lives.” She adds that she also sees this form of outreach education as a way to increase awareness of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society. “It’s a small organization, though it’s growing quickly, and I believe strongly in the educational work it is pursuing,” says Jill.

“That’s why I said my first goal for the program was to develop a one-on-one opportunity to go on speaking tours across the country, to meet kids and talk to them about exploration and discovery and new hybrid careers.” Her own hybrid career sprung from taking and later teaching diving classes, while she was a student at York University studying visual arts and graphic design. After graduating, she ran a graphic design company for a few years before following through on her love of water, selling the business in 1991 and moving to the Cayman Islands to continue diving and to hone her underwater photography skills.

In 2001, she was part of a team that explored ice caves of icebergs, where she and her first husband, fellow cave diver Paul Heinerth, experienced the calving of an iceberg, documented in the film Ice Island. “I was one of those kids who liked everything,” recalls Jill. “I always loved learning and I had some incredible mentors as teachers, who let me explore many diverse topics. Even in high school,I had a hard time deciding what to study. When I went to university, I was very interested in all the sciences and I loved geography and history.I was also a creative person and a musician.

“Eventually, she adds, “I decided to pursue fine arts almost because it was hard. When I look back on that decision, I’m incredibly grateful.There have been times in my life when I’ve wished that I had Ph.D. after my name.That would certainly have helped in getting a grant or having some of my ideas taken seriously. But, in another way, being an artist has allowed me to do so much more, because I can work with scientists and be the voice of imagination. Those ideas can strike a chord. Cooperation is critical too.” She adds that scientists are often constrained by the protocols of their disciplines.

“Scientists are often forced to specialize in one very particular area for their entire lives,”says Jill. “They don’t have an opportunity to develop a general level of technical expertise when they enter the particular environment they want to study and they certainly can’t throw out wild ideas in brainstorming. That’s just not the scientific method. They have to be very careful with their words, whereas I can be quite observational and offer ideas, which may not have passed through academic scrutiny. But they’re valid and they cause people to think.”

“I think it’s a real gift that I’ve been able to pursue this direction,” she continues. “I’m the eyes or hands for these scientists and bring them back what they need, whether it’s samples or artifacts or just the history. And the best part of the deal for me is that I don’t have to sit at a desk and analyze for the next 10 years.”

She will, however, spend considerable time writing as she has a four-book contract (two for adults and two for children) with Random House in Canada and Harper Collins in the U.S. The first of the four, an adult, nonfiction work entitled Into the Planet, is to be published in the fall. “It’s my life story of exploration framed through facing and embracing fear,” explains Jill, who has had such frightening experiences on land as being attacked by a knife-wielding burglar and being held at gunpoint in the Libyan desert, as well as surviving the many challenges posed by underwater exploration.

Also on Jill’s agenda is We Are Water. “This is a project that my husband, Robert McClellan, and I started a few years ago,”she explains. “It’s not a proper foundation. It’s just the two of us using our time and the resources from my being in other locations to meet people and talk about water literacy.It’s an effort to take my explorations and turn them into an educational and outreach initiative, an opportunity to help people understand where their water comes from and how to protect it for future generations.”

Included in Jill’s long list of prestigious awards is being named Sea Hero of theYear in 2012, when Scuba Diving magazine recognized her “for using her deep knowledge of some of the Earth’s most remote and pristine places to help ordinary people understand that water conservation begins and ends with individuals.” Her most recent awards came in 2017 when she received a NOGI Award for sports and education from the Academy of Underwater Arts and Sciences and was made a Fellow of the organization. Two months later, in March 2017, Governor General David Johnston awarded her the Canadian Polar Medal. The We Are Water project includes a documentary film and a children’s book.

Included in Jill’s long list of prestigious awards is being named Sea Hero of theYear in 2012, when Scuba Diving magazine recognized her “for using her deep knowledge of some of the Earth’s most remote and pristine places to help ordinary people understand that water conservation begins and ends with individuals.” Her most recent awards came in 2017 when she received a NOGI Award for sports and education from the Academy of Underwater Arts and Sciences and was made a Fellow of the organization. Two months later, in March 2017, Governor General David Johnston awarded her the Canadian Polar Medal. The We Are Water project includes a documentary film and a children’s book.

“We even rode our bicycles across Canada presenting that film anywhere that people would meet,” she says. “We showed it in dive shops and libraries and museums across the country.” Heinerth Productions, the company that she and her husband own, specializes in independent publishing, new media content creation and underwater videography. While she is away on exploration missions, he keeps the home fires burning and the company running smoothly.

“I realize this is a really untraditional role for a man,” says Jill, “But my husband, who has had several interesting careers, from being in music production to being a combat photo journalist and becoming a nurse and working in prison nursing, is incredibly supportive of my work.I really hit the jackpot when I met him. He is the man of my dreams.”

Her most recent project, Arctic on the Edge, is the next step in the We Are Water initiative. “Talking about water literacy is intertwined with how we’re using it and how we can preserve it for future generations,” says Jill.

Her most recent project, Arctic on the Edge, is the next step in the We Are Water initiative. “Talking about water literacy is intertwined with how we’re using it and how we can preserve it for future generations,” says Jill.

“So many of the water issues are climate change issues.” With that in mind,Jill is documenting the journey of an iceberg from Greenland, across Baffin Bay and Labrador into Newfoundland. “Talking about the changes in our northern climate extends the message about water and environmental resources and how to protect them.” The area has been severely affected by climate change, she points out.

“The Inuit elders up there remember the sea ice extending so much further and being so much thicker when they were children. Now, it takes until February for the ice to be strong enough for them to go out on their skidoos or to go on their traditional hunt on land.And by March it was already starting to melt.It’s a real time of change.” With all the traveling travelling Jill’s work entails, she has only once been able to accommodate a pet in recent years.

A kitten found her while she was out for her morning swim during the part of the year she spends in Florida. “He jumped off the bank, swam towards me, climbed onto my shoulder, tucked his little head into my neck and started to purr,”she says. “Swimmer — could I call him anything else? — was with us for 11 years.”

At this point, Jill and her American husband (she calls him “a wannabe Canadian”) are “slowly working back to permanence in Canada” — between various cave diving and mapping projects, speaking tours and filming assignments.