See her works in Outside the Lines: Women Artists at War, a new exhibition at the Canadian War Museum.

By Paul Gessell

Generally, there have been two types of war artists. The old-school ones who painted during the two world wars tended to depict soldiers as relentlessly heroic. Then came the 1960s and the Vietnam War: Artists around the western world became more critical, mainly interested in showing the horrors of war.

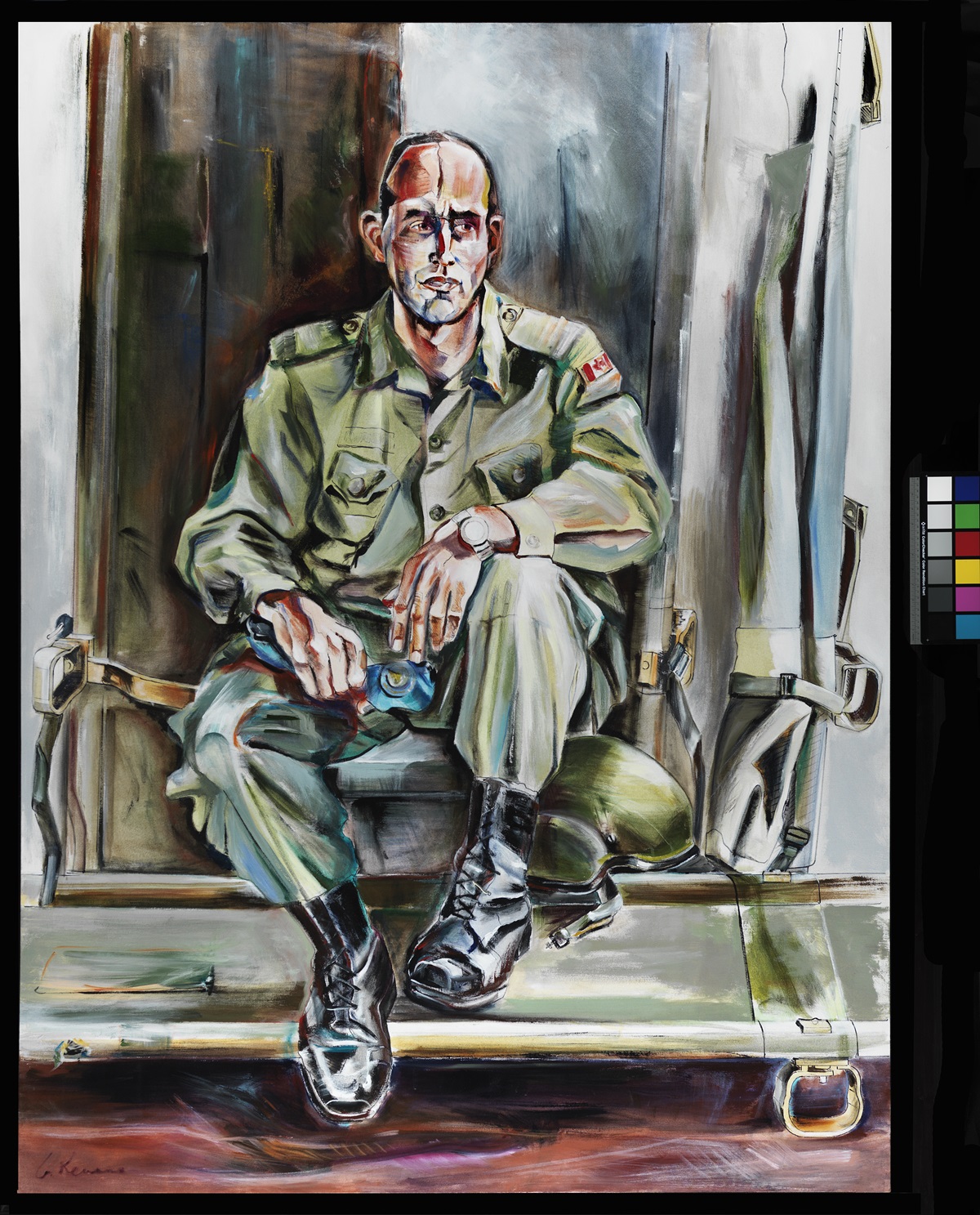

Gertrude Kearns, one of Canada’s most celebrated living war artists, fits neither stereotype. The Toronto-based artist, a recipient of the Order of Canada, is one of the stars of the new exhibition Outside the Lines: Women Artists at War, running from May 24 to January 5, 2025, at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa. A three-year national tour follows.

Gertrude has great respect for the military. That respect is largely returned. Many of Canada’s normally camera-shy military leaders dutifully sit for portraits by her, trusting the messages her art disseminates are fair and honest. Gertrude does not deify her subjects. Instead, she humanizes them, revealing their strengths and their quandaries, often with catchy slogans on the canvas, a famous one being “Keep the Peace or I’ll Kill You” attached to a portrait of General Lewis MacKenzie, once Canada’s top UN peacekeeper in Bosnia.

Gertrude has great respect for the military. That respect is largely returned. Many of Canada’s normally camera-shy military leaders dutifully sit for portraits by her, trusting the messages her art disseminates are fair and honest. Gertrude does not deify her subjects. Instead, she humanizes them, revealing their strengths and their quandaries, often with catchy slogans on the canvas, a famous one being “Keep the Peace or I’ll Kill You” attached to a portrait of General Lewis MacKenzie, once Canada’s top UN peacekeeper in Bosnia.

“Her work is very matter of fact,” says Lindsey Sharman, a former curator with Calgary’s military-themed Founders’ Gallery. “She is presenting her sitters in a non-emotional way with these very candid quotes that are not always complimentary, not always critical, but offer a lot of nuance and it’s more humanizing than a more classic type of portraiture.”

Gertrude attracts generals like photographer Yousef Karsh attracted celebrities. The day the 70-something was interviewed for this story, she was awaiting a visit from Canada’s top soldier, the outgoing chief of defence staff, General Wayne Eyre, to sit for a portrait.

Sometimes Gertrude’s paintings make the military uncomfortable and veterans angry, when the pictures reflect the hard truth of a situation. These have included paintings related to the 1993 torture of a Somali civilian by Canadian soldiers, a series of controversial portraits of General Romeo Dallaire suffering mental anguish from the Rwanda genocide of 1994 and a searing painting in 2011 of a horribly wounded Canadian soldier, a triple amputee, entitled Saved: For What?

That latter painting was partially inspired by the Fred Varley First World War scene titled For What? Varley’s painting shows a cartload of corpses about to be buried in a muddy graveyard, possibly in Belgium, where thousands of Canadian troops perished. Gertrude says the member of the Group of Seven is one of the artists who have most influenced her. Charles Comfort is another. Comfort was also an official war artist during the First World War and later became director of the National Gallery of Canada.

“For What? is one of the few official Canadian First World War paintings that does not hide the reality of battlefield death in images of ruins, blasted trees and battle detritus,” Laura Brandon, the former art curator at the Canadian War Museum, writes in War Art in Canada: A Critical History. “Kearns’s portrait of a dying triple amputee, bandaged completely out of recognition as he lies in a hospital bed, also asks whether such a fate is worth the fight.”

“For What? is one of the few official Canadian First World War paintings that does not hide the reality of battlefield death in images of ruins, blasted trees and battle detritus,” Laura Brandon, the former art curator at the Canadian War Museum, writes in War Art in Canada: A Critical History. “Kearns’s portrait of a dying triple amputee, bandaged completely out of recognition as he lies in a hospital bed, also asks whether such a fate is worth the fight.”

Gertrude has three paintings in the war museum exhibition. The Dilemma of Kyle Brown: Paradox in the Beyond is from the Somalia series, Injured: PTSD reveals an unnamed Canadian soldier suffering post-traumatic stress disorder and there is also a portrait of General Jennifer Carignan, a pioneering combat soldier.

The exhibition shows how the role of women military artists has evolved from the 18th century when Elizabeth Simcoe sketched a York military barracks to Mary Riter Hamilton from the First World War and Molly Lamb Bobak from the Second World War to Barb Hunt, whose contemporary works include a pink, knitted anti-personnel landmine.

“Earlier, women painted what they were seeing,” said Stacey Barker, curator of the exhibition. “They’re not making a statement.”

Gertrude, like many of her contemporaries, makes statements. She paints more than the obvious. She dives right into the conscience of her subject. She also faces dangers her predecessors didn’t. In 2006, she narrowly escaped being killed by a suicide bomber in Afghanistan while travelling with Canadian troops.

National prominence came to Gertrude in the 1990s, in large part because of Laura Brandon, the retired war museum curator who frequently exhibited her work. Brandon, not one known to exaggerate, simply calls Gertrude “tremendous.” People from coast to coast will be able to judge for themselves as iterations of Outside the Lines tour the country for the next three years.