Love of Space

By Stephen Johnson

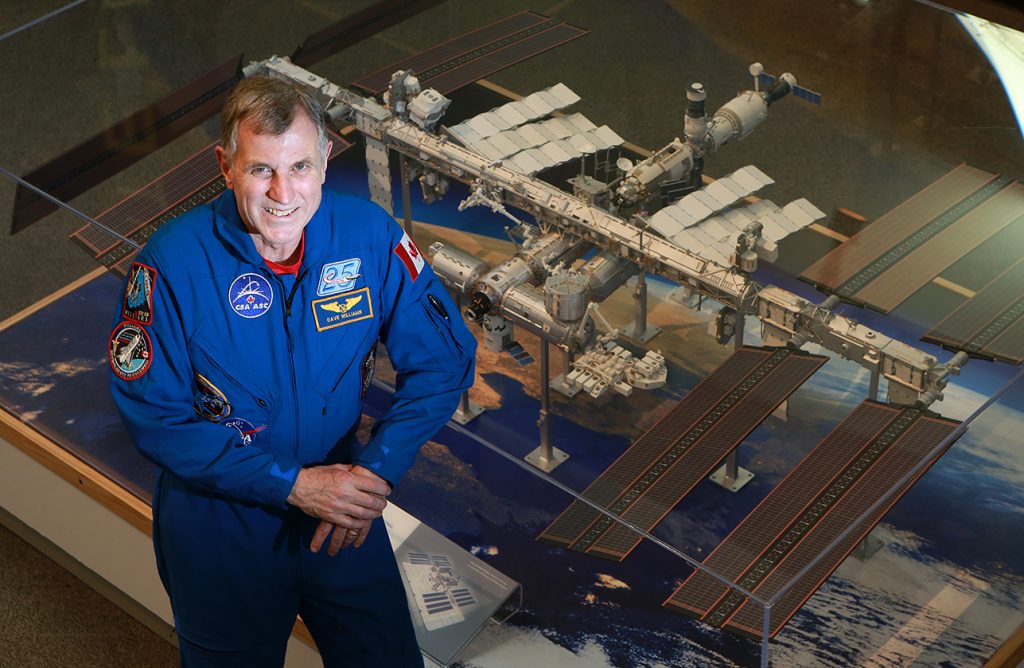

Dr. Dave Williams is someone who is not afraid to admit and even embrace his failures. This might seem surprising considering he is a scuba diver, surgeon and renowned astronaut. His life adventures are now chronicalled in his book, Defying Limits, Lessons from the Edge of the Universe.

When Dr. Williams was born in 1954, space travel was only starting to be considered a possible reality. The advent of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union accelerated the process. Yuri Gargarin became the first person to orbit the earth in April 1961. It was another astronaut who would inspire Dr. Williams. “I remember watching Alan Shepard’s launch on our old black and white television,” reminisced Dr. Williams. “The date was May 5, 1961, it was 11 days before my seventh birthday. Walter Cronkite provided the commentary. I still remember the moment of lift-off and how the 15-minute sub-orbital flight inspired me to want to become an astronaut.”

He also credits his childhood and parents in helping to foster a desire to learn and resilience — skills that would serve him well as an astronaut. “Growing up in the west-end suburbs of Montreal, we were surrounded by forests and streams,” remembered Dr. Williams. “Our parents let us go and explore nature. When you are a 10-year-old building fires in the woods, it is important to figure out how to start a fire without burning yourself and the whole forest down.”

Besides allowing Dr. Williams to explore, his parents actively encouraged his interest in science. “Mom delighted in turning her kitchen table into a lab. One of the many things she ordered for us was a dissecting kit, which she proceeded to teach us how to use. But if I got the exploration gene from anybody, it was from my father. In 1967, when I was twelve, he enrolled me in scuba lessons. The only way I made it into the class was because my father negotiated with the instructor on my behalf.” With a lot of hard work and studying, Dr. Williams became a certified diver shortly after his 13th birthday and nine years later would become a certified instructor.

Dr. Williams graduated high school in 1971 with the standard issue long hair and motorcycle of the time. He entered McGill with the idea of a career in life sciences or medicine. Things didn’t come easy for Dr. Williams during his first few years at McGill. “I was working a couple of part-time jobs to pay for my tuition while trying to study. When my marks came in at the end of the year, I was barely passing, and my marks were not near good enough to get into medical school. If my marks did not improve, I risked failing out of school.”

His marks did turn around enough to earn Dr. Williams a Bachelor of Science and entry as a grad student into the department of physiology at McGill. Even though, academically, things had improved, not everything was perfect. Unfortunately, Dr. Williams father’s health was not good, and he passed away in September 1976. This understandably affected Dr. Williams, with him failing a presentation to go directly into a Ph.D. program and also being turned down to get into medical school. Dr. Williams approached those setbacks with resilience. He re-focused his attention and re-applied to medical school, gaining acceptance to start at McGill in September 1979.

During this time, Dr. Williams was not all work and no play. He met his future wife, Cathy, while working at the Pointe-Claire pool in December 1978. One of their earliest dates can best be described as memorable. “I was really excited when I picked her up in my car, which I’d purchased for $50 and painted using spray cans from Canadian Tire,” said Dr. Williams. “The driver’s side door didn’t close, and I couldn’t afford to fix it, so I tied a sock around the handle and kept the other end tucked under my leg to stop the door from flying open while I drove.”

Despite the unique vehicular situation, the love between the two grew, with marriage in 1986. It helped that both individuals had personal goals as well. Dr. Williams completed his medical degree and residency, while Cathy completed her flying hours, eventually leading to a job as a pilot with Air Canada.

It was a chance meeting at a Women in Aviation Conference where Dr. Williams would reignite his passion to become an astronaut. “I had the chance to meet Linda Goodwin, an American astronaut, who had flown in space just weeks earlier,” remembers Dr. Williams. “She informed me that the Canadian Space Agency would be recruiting a new group of astronauts in 1992.”

Dr. Williams put forward his name after seeing an ad in the Globe and Mail from the Canadian Space Agency seeking applications to become an astronaut. He was one of 5,300 people to apply and after several months was invited to a final weeklong round of tests and interviews with a select group of applicants. He cleared the final tests and was informed two weeks later that he was one of four to be selected to the Canadian astronaut program. “I learned the names of the other candidates — Julie Payette, Chris Hadfield, and Rob Stewart. Many wonderful things had happened in my life and I had overcome more than a few hurdles, but the news still seemed unbelievable.”

The training program involved many different facets including gliding, skydiving, flying, scuba diving, spacecraft systems and robotic systems. A particularly challenging training regime was to fly in something called the Vomit Comet. “In space, our job would be to successfully conduct science experiments in a zero-gravity environment. The only way to simulate that, was to fly endless parabolas on the Vomit Comet to get used to performing tasks and using tools while floating weightless.” The tests took place in Houston with Dr. Williams getting by without so much as an upset stomach.

In 1993, Dr. Williams was appointed manager of the Missions and Space Medicine Group within the astronaut program. During this time period, Dr. Williams’ personal life changed — his wife gave birth to their first child, Evan, who was diagnosed with Down syndrome. After the initial shock, Dr. Williams and his wife re-grouped.

“Our goal was to raise Evan just as we would have if he didn’t have special needs. We still saw a future in which we would toss the football around, play basketball and even ski together.”

By 1995, he was picked as a NASA mission specialist to serve aboard the space shuttle. Before going on the space shuttle Columbia in 1998, Dr. Williams would undergo further extensive training and would also move to Houston, Texas.

Several weeks before the space shuttle mission, a traumatic incident occurred that almost derailed Dr. Williams’ participation on the flight. While sitting at home, the doorbell rang and a neighbour from down the street asked, “Do you know CPR?” Dr. Williams did know CPR and rushed to assist a teenage girl who was passed out on the pavement and was not breathing. She had experienced a severe asthma attack. Dr Williams applied CPR and was able to resuscitate her. He was breaking the strict protocol of his quarantine period before the space flight. Luckily, the girl made a full recovery and Dr. Williams did not get sick allowing him to make the flight.

On April 17, 1998, Dr. Williams’ life would permanently change — he would go into outer space. Dr. Williams describes the first few minutes of space flight. “The first few seconds were violent. I felt the roar of the engines more than I heard it. After two minutes of punishment, there was a massive boom and a bright orange light flashed outside the shuttle. The transition was like driving down a dirt road in the back of a pickup truck at 80 km an hour and then suddenly going on a smooth ride on perfect, unblemished pavement.” Dr. Williams had just experienced the solid rocket booster separation.

There was still more to come. “As we passed through the final layers of the earth’s atmosphere, the view outside the window grew darker and darker,” remembers Dr. Williams. “The G-forces built to three times normal in the last minutes before the main engine cut off. It felt like an elephant was sitting on my chest.”

The main engine would cut off, allowing the pressure to be released and the chance to experience weightlessness. “For the first time outside of the simulated condition of the Vomit Comet, I was experiencing true weightlessness. I admired the majestic view of our blue planet. “Spectacular,” I said to myself. I took a deep breath, trying to savor the fact that my dreams had finally come true — I was in space!”

The trip aboard Columbia was much more than just a sightseeing trip. Dr. Williams had to adapt to life in space, including how to eat and brush his teeth in weightlessness. There were also numerous scientific experiments to be conducted including many about brain adaptation.

In total, Dr. Williams spent 16 days on the Columbia. There were many special moments including seeing Mount Everest and the Himalayas from the vantage point of the flight deck, while riding an exercise bike.

After returning to earth, Dr. Williams did not rest on his laurels. He accepted a position with NASA as director of the Space and Life Sciences Directorate. His responsibilities included leading programs to protect astronauts from the hazards of the space environment.

While serving as director, Dr. Williams had the unique opportunity to serve as an aquanaut at the Aquarius underwater laboratory located off the Florida Keys. The idea was to simulate conditions on the space station, but underwater. “Aquarius resembled a large RV camper underwater: it was big, long and yellow. I reflected on the differences between living in space and living underwater. At night, the external habitat lights cast a bluish glow into the surrounding water. The viewing port was surrounded by reef fish of every color, and every now and then a barracuda would swim past.”

In late 2002, Dr. Williams gave up his role as director of Space and Life Sciences to be assigned another space mission. He was scheduled to fly to the International Space Station in the winter of 2003, but would have several setbacks before going on his final mission. On February 1, 2003, the space shuttle Columbia was returning from a 15-day mission when it broke apart upon re-entry.

Dr. Williams knew all the crew members and they were friends. “We spent hundreds of hours together in simulations, seminars and training sessions. I’d been looking forward to sitting down with them over a cold beer and hearing stories of their mission. Now, neither their families nor any of us, would ever see them again.”

In 2004, Dr. Williams was diagnosed with prostate cancer further derailing his plans. Dr. Williams had surgery and the cancer was successfully removed. It felt strange for Dr. Williams to go from being the doctor to the patient.

After his successful fight with cancer, Dr. Williams did have to excuse himself from another underwater mission with Aquarius, but was approved for spaceflight.

Dr. Williams had a chance to go into space again on August 8, 2007. This time, it was a mission aboard the International Space Station. Dr. Williams would perform his first spacewalk. “As I slid out of the airlock feet-first, everything was dark. Totally, absolutely dark.”

Soon enough, the sun passed by, changing the experience for Dr. Williams. “I felt the sun, before I saw it. My back was to the earth and I felt myself getting warmer as the station grew brighter around me. It was more than just the sun’s warm embrace, though: I sensed its life-giving nature seeping into my suit, as though to say, everything is going to be all right.”

Dr. Williams would go on to perform two other spacewalks on this mission, giving him the most spacewalks of any Canadian.

Dr. Williams retired from the space program in February 2008 and took a number of jobs in the medical field, including CEO of a hospital in Newmarket, Ontario.

“It is easy to long for the rush that comes from an adventure or the thrill of accomplishment, which can sometimes make our day-to-day experiences feel flat by comparison. But the truth is that those moments in-between are opportunities to cherish as well. The quiet of the early morning with the smell of fresh coffee and the sizzling of bacon cooking on the stove; the raw power of the thunderstorm with winds roaring through the trees; the innocence of your infant child falling asleep on your chest — those moments are as important as the others, and if we don’t pay attention, it is easy to miss them.”