by Iris Winston

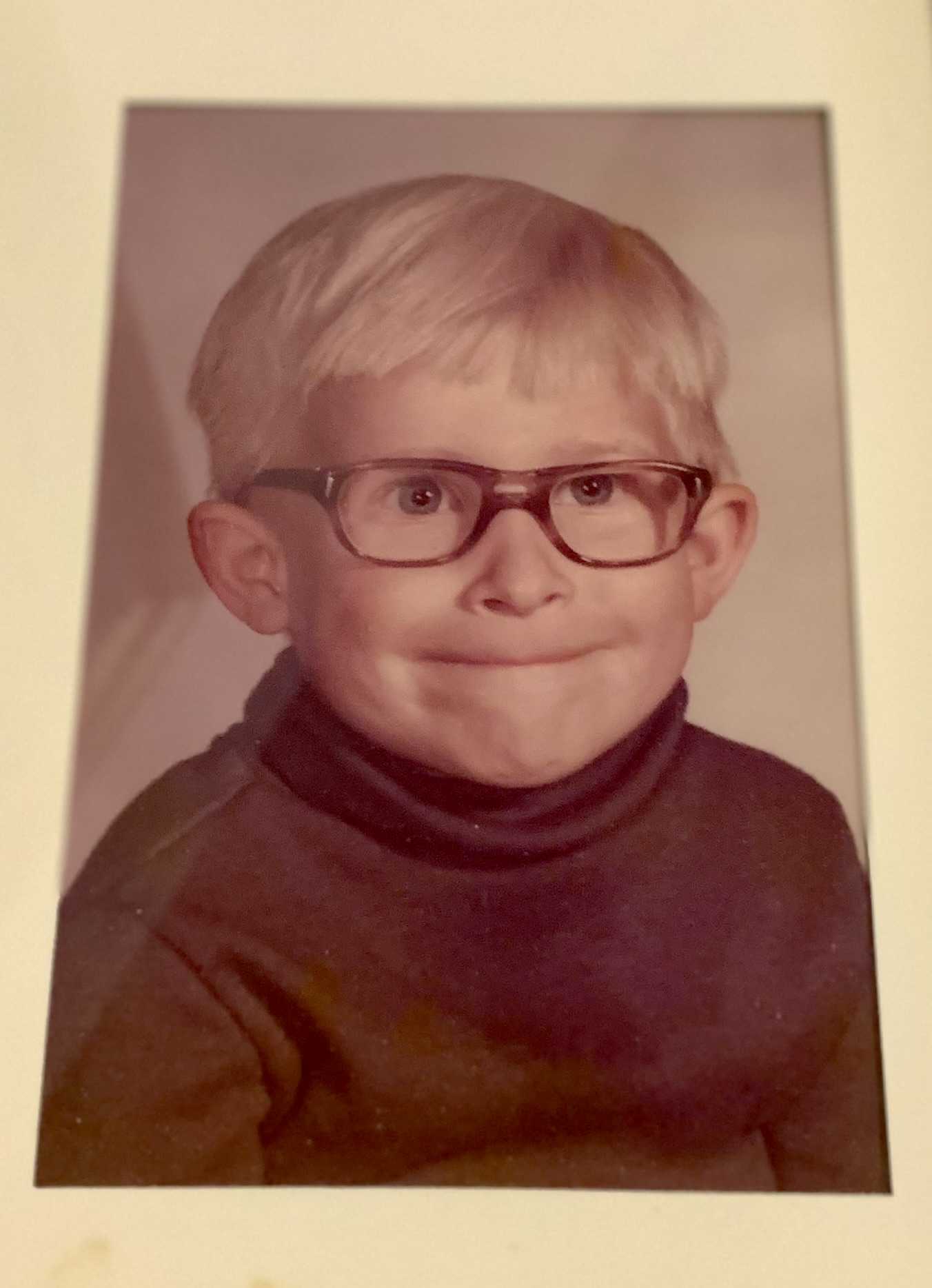

There’s a new baby next door. She’s beautiful, alert, active and very interested in the world around her. As parents, relatives and friends smile and see how quickly she’s developing, thoughts of possibilities for her future flash through their minds.So it was when my oldest child, Alex, was tiny. I remember a particular afternoon when, at around nine months old, he was playing with alphabet bricks. The scene was peaceful with the dog asleep at my husband’s feet, as we read, glancing up occasionally to watch Alex.

The atmosphere changed when he placed a second brick neatly on top of the first. It grew positively electric when he added brick number three to the stack. And when he reached for a fourth brick, we were really excited.

After all, didn’t the Denver Developmental Screening Test say normal nine-month-old babies could stack two or three bricks? Even the dog woke up as brick number four was added to the tower. Then, brick number five made it (slightly angled, but relatively steady). The dog, happy we were smiling so proudly, wagged her tail, striking Alex’s edifice to the ground. But we had seen it and knew our boy had a great future:

MY SON, THE ARCHITECT.

A couple of years later, his career direction changed. He became the great experimenter, conducting such tests as throwing dog toys into the toilet, flushing and waiting to see whether the dog attempted to follow. (The answers were: His mother developed expertise with a plumber’s auger. The dog lost interest in the toy.)

Fortunately, MY SON, THE PLUMBER was a short-lived phase. Investigation, however, continued.

Very early one morning, he appeared at my bedside and gave me a handful of little knobs. Sleepily, I reached for the bedside lamp. This is when I discovered the origin of the knobs. Alex had collected the switches from all the table lamps in the house. I was torn between irritation at being inconvenienced and pride that a three-year-old could make such connections. Pride won and I hugged MY SON, THE ENGINEER.

A few months later, he decided it was time to party. After his parents were safely in bed, he opened his bedroom door, headed for the living room and turned on the radio and the lights. On that occasion, MY SON, THE PARTY ANIMAL was returned to bed in short order.

Entertainment and performance remained important through his childhood. Memories of school plays and musicals flash by. I see a small boy clanking his chains as Marley’s ghost, a medium-sized kid mourning the King of Siam, a suave youth smiling wickedly as Mordred, watching the walls of Camelot crumble.

MY SON, THE PERFORMER.

From a very young age, Alex went his own way. He decided to read the Bible from beginning to end and dragged his mother to church each week. He asked to join a religious studies group and the local United Church minister created a junior version for him. He then persuaded his friends to join him, and the Bible Buddies met regularly for the next two years.

MY SON, THE ARCHBISHOP.

He decided that managing money and saving for his university education were essential. At 14, he made an appointment with a financial advisor to discuss how he should invest the $500 he had accumulated after babysitting, doing a paper route and saving his pocket money.

MY SON, THE FINANCIER.

Years earlier, a hospital stay sparked his interest in medical matters. At age seven, he expressed great concern when a nurse placed an oxygen tent over the patient in the next bed. “Don’t they know that plastic bags are dangerous?” he asked. He also watched with interest as the doctor listened to his back and chest through a stethoscope. “If you’re looking for my heart, doctor, you’ll find it a little lower and on the left,” he advised.

MY SON, THE DOCTOR.

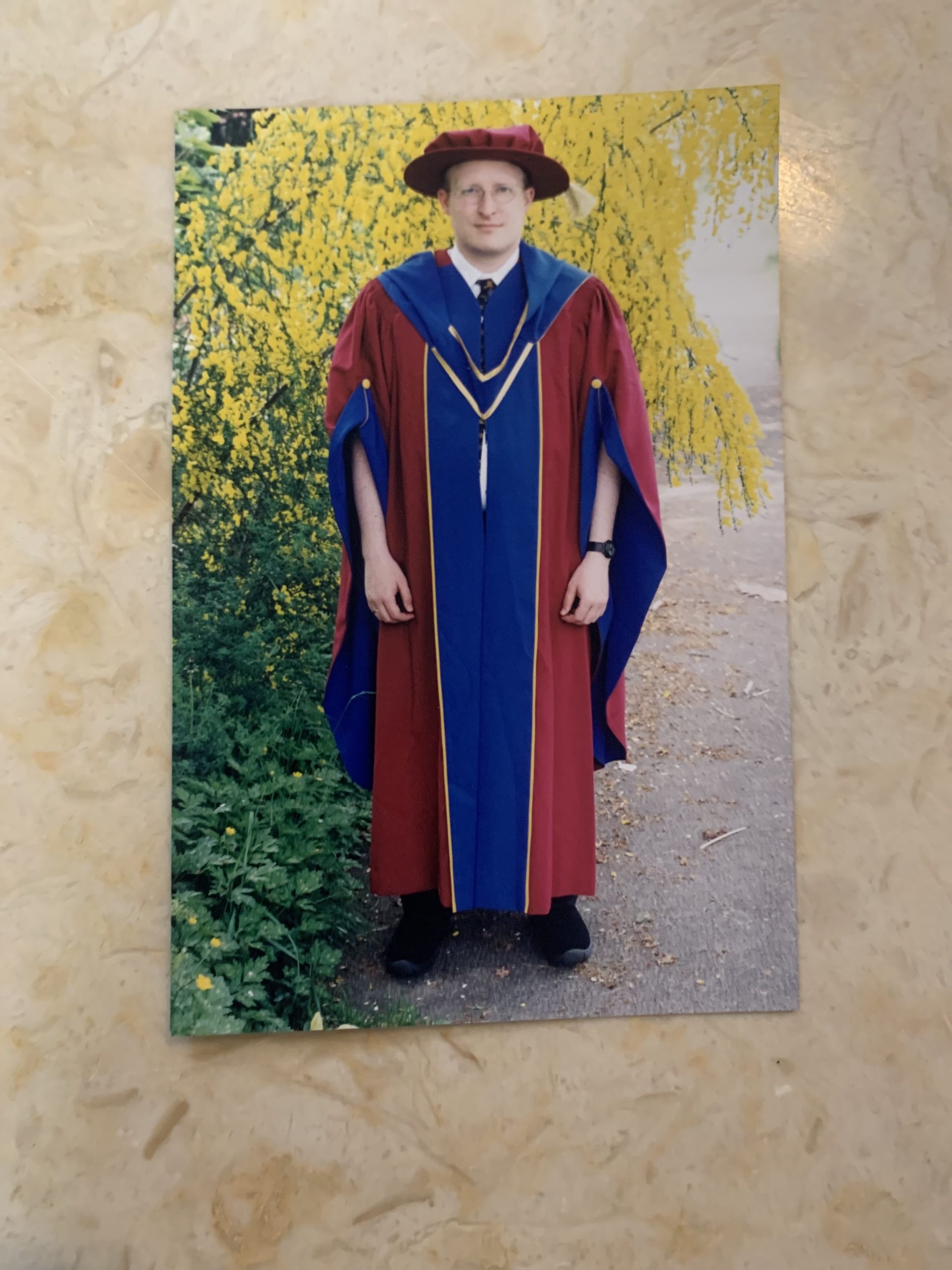

Alex eventually moved along a career path different from any I imagined along the way. For all his professional working life, MY SON, THE PHILOSOPHER has been an instructor or department head at Langara College in Vancouver. Now, with a family of his own, he is likely imagining career possibilities for his growing daughter.