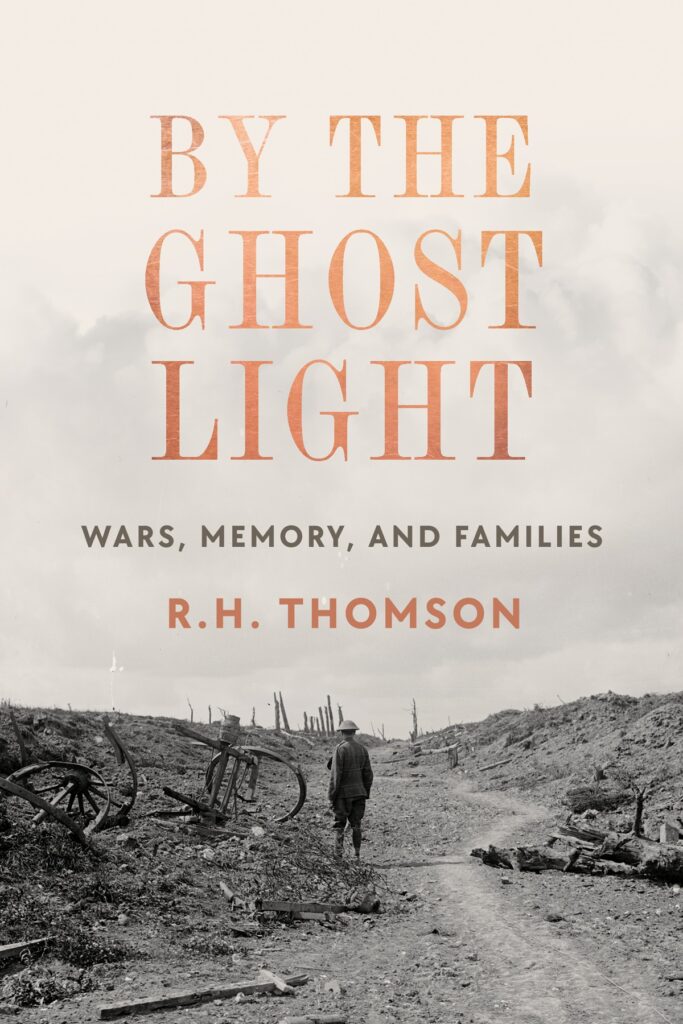

Acclaimed Canadian actor R.H. Thompson has played many characters. His other leading role is as creator of a global memorial for people of every nation killed in the First World War.

By Jamie Portman

Perhaps it was the haunting moment when veteran Canadian actor R. H. (Robert Holmes) Thomson visited Flanders and stood on the battleground where a great uncle had died a century ago.

Or maybe it was the excitement he experienced when a visit to a decrepit building in Moscow offered hope that it would help fulfill a dream that was consuming his life.

Or possibly it was reading yellowing letters from the past written in the midst of carnage. They too brought substance to his mission to give a name to each of the 9.5 million soldiers killed in the First World War.

In sorting out the many emotions he has experienced in the course of this quest, Robert Thomson now says the most meaningful ones are the most personal. “It’s when someone comes up to me and says, ‘Thank you for doing this.’ ”

Thomson’s non-profit organization, The World Remembers, was responsible for projecting the names of the war dead of all countries on an outdoor screen near Toronto’s old city hall a few summers ago. It continued for 28 nights, and kindled some moving responses. For Thomson, the impact on people of ethnic backgrounds was particularly significant.

He remembers a touching encounter with a woman of German extraction. “I was born here but my family came from Germany in 1947,” she told him. “So being German Canadians, we just went quiet when November 11 came around. But seeing the German names on that screen along with the Italians, the British, the Americans, the Australians, made me think that remembrance can be for everyone.”

Thomson, now 77, is one of Canada’s most honoured actors, recently winning accolades for evoking the world of Green Gables with his portrayal of Matthew Cuthbert in the television series Anne With An E. So despite his continuing commitment to The World Remembers, performing is still very much part of his life.

“It drives me nuts because I don’t have any time off,” he laughs. “But the creative part is still the creative part.”

His creativity extends to writing. Last year saw the publication of By The Ghost Light, a riveting exploration into how nations remember their war dead. Two decades previously, he wrote a play, The Lost Boys, based on the letters his five great uncles wrote from the 1914-18 battlegrounds. Two died in battle. Two others returned home permanently damaged and died before their time.

Their legacy planted the seed for The World Remembers. And their

names were among the thousands projected on a wall opposite Belgium’s Flanders Field Museum—another example of the First World War centenary observances spawned by Thomson’s passion to achieve a unique, lasting global memorial.

“We now have a database of five million names. We’re trying to collect the names of everyone killed in that war: nobody has ever done this before—anywhere. And we now have 26 countries signed up.” The most recent additions are Malta, Portugal and (surprisingly) Japan.

It turns out Japan had vessels in the Mediterranean during the war. As for Portugal, it has provided “amazing” photographs for the magnificent photo gallery available to anyone accessing the organization’s website, theworldremembers.org. The needs of the gallery are specific. The focus is not on “the more formal images of war, of this or that general doing this or that.” Instead, the emphasis is on a more personal and human dimension: “The people of the war, a soldier, a nurse, the person who brings bread to the wounded.”

This remarkable project has survived through private and public funding. “We’re always needing money,” Thomson concedes. At the time of this interview, he’s in pursuit of $87,000 to upgrade the software for The World Remembers kiosks at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa and the American War Museum in Washington.

Meanwhile, the quest for the names of the dead continues.

“Yes, we now have a database of five million names, yet we’re just over halfway. We’re never going to get all of them because so many records were destroyed.”

But he and his colleagues keep trying. A French military attaché aided in the addition of some 1.4 million names to the record. But casualty counts from the United States, of all countries, have been frustratingly awash in ambiguity. And then there is Russia.

Thomson never received a reply from his letter to Vladimir Putin requesting Russia’s participation in the project. However he did find himself visiting a “strange military archive” in a decrepit Moscow building and finding tattered records that even the Russian military knew nothing about. “We think we have a million names in these books,” the two archivists told Thomson. Did they have another copy? No. Had they been photocopied, microfilmed, scanned? No, no, no.

Thomson never received a reply from his letter to Vladimir Putin requesting Russia’s participation in the project. However he did find himself visiting a “strange military archive” in a decrepit Moscow building and finding tattered records that even the Russian military knew nothing about. “We think we have a million names in these books,” the two archivists told Thomson. Did they have another copy? No. Had they been photocopied, microfilmed, scanned? No, no, no.

“This was supposed to be a high-grade archival building,” Thomson says incredulously. He had always known that negotiations with Russia would be complicated. Now, though, he saw a potential backdoor to achieving his ends. But then Russia grabbed Crimea in 2014. Next came the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, a country already signed up. The dynamic changed for the worst. “The story of Russia in the First World War is immense,” Thomson says ruefully, concerned it may now be beyond his grasp.

Asked about traditional Remembrance Day observances, Thomson suggests that, while honourable and necessary, they are set to a script written in 1920—a script that needs refreshing. “There is the traditional path of remembrance, but I’m suggesting there can be a broader path to be walking down.” This new path, forged through The World Remembers, recognizes all the people, from every nation, who lost their lives in that first global conflict.