A Perfect Plot

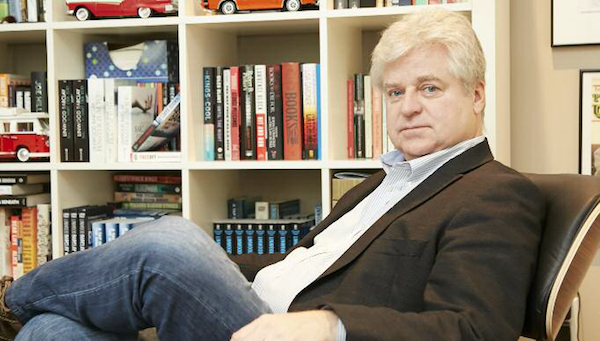

Bestselling author Linwood Barclay’s crime thrillers

keep readers wanting more

By Jamie Portman

Photos by Ashley Hutcheson

If you visit the study where Linwood Barclay writes his hugely popular crime thrillers, you’ll find that one wall is rapidly filling up with framed bestseller lists.

Don’t assume, however, that these lists are confined to Canada, where his books have built a massive fan following over the past decade. Linwood consistently makes the charts overseas as well.

“Any time a book of mine goes to No. 1 in the United Kingdom, they frame the bestseller list from The Sunday Times, and they send it to me,” he explains.

Sometimes, he doesn’t quite get there, but Linwood is philosophical about such occasions. After all, this home-grown Canadian author points out, he can’t really be miffed if someone like Dan Brown, of Da Vinci Code fame, nudges him out of top spot, which is what happened with Linwood’s ac- claimed 2013 novel, A Tap At The Window. There’s also the astonishing example of No Time To Say Goodbye, the novel whose central situation emerged unexpectedly from his subconscious at 5 a.m. one morning and ended up changing his life.

“That book came out first in Germany and there was a period of time in 2007 where the only person outselling me in that country was J.K. Rowling,” he says incredulously. “And then in the U.K. it became the bestselling novel of the year.”

As someone who less than a decade ago was still grinding out a hugely successful column for the Toronto Star and only dreaming of success as a novelist, he keeps wondering how long his current popularity will last.

Linwood turned 60 in 2015, and he knows it’s a milestone. And, as someone who less than a decade ago was still grinding out a hugely successful column for the Toronto Star and onlydreaming of success as a novelist, he keeps wondering howlong his current popularity will last. He’s inherently conservative about such matters, perhaps because of early hardships. Indeed, when he looks at the symbols of success — nearly six million copies sold worldwide in 40 different countries, the TV and movie deals, the cocktail named after him available in the Library Bar of the Royal York Hotel, the two Porsches in the garage of his luxury Oakville home — he still finds the whole thing rather surreal.

“I think there’s a part of me that expects it to end every day,” he confesses. This in spite of the fact that his sales continue to increase each year and that his current contracts will take him through most of the current decade. “So I’m amazed to be doing this now and having the success I’ve been having.”

At the same time, for all his professionalism — and Linwood Barclay is a disciplined professional — there remains a boyish enthusiasm about the wonderful things that keep happening to him. He produces a photograph of himself and Stephen King, taken during a PEN Canada meeting.

“Just bragging here, but this is the coolest picture,” he grins. “Me on the right and that’s Mr. King on the left. We’re both patrons of PEN Canada. And as you know, he’s been a fan of my stuff for a few years and was coming up here. When he showed up, the host said, ‘Stephen, here’s somebody I’d like you to meet.’ And Stephen turned around and said, ‘Oh, my God — it’s you!’ And he threw his arms around me.”

That’s not the end of the story. “I was insufferable for days,” Linwood adds mischievously. “You couldn’t live with me for days. I was just terrible.”

Linwood isn’t indulging in name-dropping here. It’s more admitting to hero worship and emphasizing how much the endorsement of his peers means to him. He talks about a U.K. book tour in 2013 and the day the legendary Ian Rankin, creator of Inspector Rebus, interviewed him before 600 people at the Cheltenham Book Festival. “That’s one of the coolest events I’ve ever done.”

So, despite the iron-grey hair, and the kind of clear-eyed pragmatism that comes only from the experience of living, the excited kid he once was still lurks within him. Recently, he was in Ann Arbor, Michigan, as part of a tour promoting his latest novel, No Safe House. “I wandered into this store and they had these Batman logo cufflinks. I thought about them for the longest time — they cost 180 bucks or something — and I ultimately didn’t get them. I think now it was a big mistake.”

Batman? Really? Indeed, yes. Linwood has been a huge fan of the caped crusader since childhood, and his study walls also include eight or nine examples of valuable background art from the animated Batman series that flourished on television in the early 1990s.

“I like Batman,” he says forthrightly. “When somebody asks me what literary character I’d like to meet in real life, I usually say Batman.”

And he still loves toys.

“My son and I go to model train events and flea markets and stuff like that. I’ll see a toy from my childhood and hem and haw about whether to pick it up.

“As a kid, I had this lovely tractor-trailer that Dinky Toys made, and every once in a while I see one of those at an antique fair and it’s like $500 and I think, ‘Do I want it that badly?’ One of these days I’ll probably say, ‘What the hell.’”

There remains an everyman quality about Linwood, whether he’s matter-of-factly contending that writing bestselling books is simply his particular way of earning a living, or whether he’s rhapsodizing about his life-long love affair with model trains. You would never call him hip or trendy. In many ways, he’s the classic suburbanite who resists living in big cities. And he has an old-fashioned belief in the resilience of the human spirit.

Linwood’s brilliantly plotted thrillers thrust ordinary people into desperate and frightening situations and allow us to see how they respond. A missing child, a terrorized family, the terrible consequences of innocently picking up a hitchhiker, a home invasion — these are fictional elements that tap into real-life fears.

Linwood understands what Stephen King meant when this American icon confessed that much of his writing was sparked by a fear of terrible things happening to his family.

“Oh God, yes. Absolutely,” Linwood says by way of agreement. “What could be scarier than some- thing happening to your family?”

And if it happens in the leafy tranquility of the suburbs, you have the formula for a typical Barclay novel.

“I know suburbia. I’ve never lived in a big city. I live in the suburbs and even when I had a job at The Star I stayed in the suburbs. I’ve known small towns from childhood. I don’t know big, dense cities. But I think it’s true that people are people everywhere, whether it’s the suburbs or the city — and people have secrets and people have things they don’t want you to know. And there are bad people in the suburbs and bad people in small towns, so that’s where I put them.”

It’s been said that the child is father of the man, and Linwood’s faith in the ordinary individual is shaped by his own sometimes difficult history. He was born in south-western Connecticut in 1955, and his parents moved to Canada when he was four. His father was a commercial artist. “So if you were to look at LIFE Magazine or the Saturday Evening Post back in the 1950s and saw illustrations of cars in the advertisements, there was a very good chance he drew those cars.”

Everett Barclay was lured to Canada by William Templeton Studios, a leading Toronto advertising agency, only to find his particular craft in jeopardy a few years later.

“As the ‘60s progressed, illustrations started to nose-dive as photography took over. The car ads became photographs — they weren’t illustrations anymore.”

As a “fallback” measure, his parents purchased a cottage resort on the shores of Pigeon Lake in 1966. “Over a period of time, we ended up moving there permanently to run this summer resort business,” Linwood says. “But I ultimately took over the running of it when my father died. I was 16, and he contracted lung cancer and went in for surgery just around the time when I was able to get my licence to drive. That would have been in March or April of 1971, and by November he was dead.”

Linwood and his father were close, and he’ll never forget the last of their nightly chess matches. The cancer was spreading and suddenly Everett Barclay found himself unable to continue because he had forgotten how to move the pieces.

“My father had taught me to play chess and there I am at the age of 16 and he can’t remember how the knight moves. Yes, that was tough.”

Linwood’s mother, Muriel, couldn’t cope with the demands of running Green Acres on her own. “My mom was nominally the manager of the place, but I basically did all the grunt work, so I ran that place for several years, until I was 22 when I got married and went to work for a newspaper. It was an interesting period in my life. I wrote a book about it called Last Resort. It’s out of print but can be downloaded.”

Meanwhile, this was a kid who’d had an urge to write since Grade 3. He was always trying his hand at short stories and novels. He was also a voracious reader who was collecting Hardy Boys books in Grades 3 and 4 and had graduated to Agatha Christie by Grade 5, and the stylish crime fiction of Rex Stout in Grade 7. Then, as a teenager, he discovered the hard-boiled novels of Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, and especially the great Ross Macdonald, who would have a profound impact on him when they met a few years later.

While attending high school and then nearby Trent University, home responsibilities continued to mount.

“Those years from 16 to 22 were probably the most pivotal years of my life. I was there in the room when my father died; I had all this responsibility thrust upon me. I was looking to these — I don’t know — surrogate figures; older men who were camp guests and often helped me to do things because they knew I needed life advice on how to fix a leaking pipe.

“I went to Trent because it was a half hour’s drive from the camp, so because we didn’t close until Thanksgiving, I would still be coming home from school each day to clean the boats and bury the fish guts.”

Linwood triggered a major crisis when he announced following university that he wanted to leave home.

“My mom made a living hell for me because she wanted me to stay and run it. What I did wasn’t rocket science. I rented boats and motors and I cut the grass and I fixed broken docks. She ultimately ended up hiring somebody to do what I did, but she didn’t want me to go.”

But there were other family concerns — a mentally ill brother who was 11 years older than Linwood. “So I was taking care of him as well as helping my mom.”

More than three decades later, Linwood would have one of his greatest successes with Trust Your Eyes, a gripping thriller in which the narrator’s brother is a schizophrenic who accidentally views a murder on a computer program similar to Google’s Street View. The novel, so sensitive in

its empathy for the mentally ill, has been optioned by Warner Brothers for a movie and is dedicated to Linwood’s brother.

Several factors contributed to his decision to break free and concentrate on writing. The first was meeting Neetha Sands, an anthropology major, who sat next to him at some of his classes at Trent. She was a year ahead of him, and after she graduated and enrolled in the faculty of education at the University of Toronto, their romance continued.

“We’ve been married 37 years, so it’s working out,” Linwood smiles. And yes, Neetha has been a tower of strength. “I don’t know how she does it,” he adds fondly.

Another factor was the late Margaret Laurence, the revered Canadian novelist who came to Trent as writer-in-residence while he was a student.

“She was very good to me. We remained very close friends until she passed away. She was able to meet with students and take time to read their work, and then they would come back for a second appointment so she could critique it.”

When Linwood was recently invited back to his old university for a brief stint as writer-in-residence, he said yes immediately. “I felt I absolutely owed it to Trent — and to her. It was so nice to be back and to walk around the grounds. It felt just like yesterday, but it was 36 years since I’d left there.”

A third factor was the friendship that sprang up with Kenneth Millar who, under the pseudonym of Ross Macdonald, had produced a series of internationally acclaimed crime novels. During his third year at Trent, Linwood was working on an essay about private-eye fiction and wrote Kenneth asking about the origins of his famous protagonist, Lew Archer. He received a warm reply from Kenneth who also sent him a copy of his new novel. When Linwood sent him samples of his writing, Kenneth said they showed great promise.

The veteran master of detective fiction continued to correspond with his young protégé and even showed up in Peterborough on one occasion. The two had dinner together — and,as Linwood told Toronto Life magazine a few years ago, “It was akin to a baseball fanatic spending the day with DiMaggio.” The crowning moment came when Kenneth signed Linwood’s copy of his latest novel along with the message: “. . . for Lin- wood who will, I hope, someday out-write me.” When Linwood left Trent University, he naively dreamed of a career as a writer of bestselling novels, but suffered a rude awakening when his youthful fiction kept being rejected.

“I think the reason was that they were no good,” he says wryly. “So obviously that plan wasn’t going to work. Then I thought, ‘OK, where do you get paid money to write every day?’”

The answer was obvious — newspapers. So he became a reporter on the Peterborough Examiner in 1977 for $125 a week, “which back then was not a lot of money.” Two years later, he was at the Oakville Journal Record earning $240 a week, “and I wondered what I would do with all that money!” But in 1981, the paper acquired a new owner, the Toronto Star, which also owned a competing publication. This led to the death of Linwood’s own paper, and he again found himself looking for work. This took him to The Star where he went through a succession of “middle-management” editing positions over the years.

But he still wanted to write, and the opportunity came in the early 1990s following the death of the paper’s legendary columnist, Gary Lautens. Linwood was successful in a bid to take over that slot, and for the next 14 years, he built up a huge readership with humorous columns on everything from family living to more barbed attacks on the Ontario government of Conservative premier Mike Harris. “I hated that guy and still do,” says Linwood, who published three books of humour during this period, one of which was entitled Mike Harris Made Me Eat My Dog.

He loved being a columnist, but still wanted to write fiction. This led to four comic mysteries featuring a character named Zack Walker, who in one book describes himself as “…a 13-year- old boy trapped in the body of a 41-year-old man” — a label which might easily sum up Zack’s creator, given the elaborate model-train display that dominates the Barclay basement, as well as that treasured Porsche Cayman, which he proudly calls his “kiddie toy.”

But despite good reviews, the Zack books weren’t selling that well. It was a moment of reckoning for Linwood who saw his fictional career at a standstill. Some magazine profiles have suggested he was at the point of desperation in his quest for fictional success, but Lin- wood doesn’t see it this way. But he was making a measured appraisal of his future, spurred on by his loyal agent, Helen Heller, who was urging him to strike out in a new direction.

“It’s time to try something different,” she told him. “Funny thrillers are a very narrow niche market of the crime-fiction spectrum. You need to do a stand-alone thriller. It needs to be darker, and it needs to be a ‘big’ book.”

Linwood decided to take her advice. If he was desperate at all, it was over finding a good plot. For a time, that eluded him, and then at 5 a.m. one morning, everything changed. He had awakened early, brooding over her directive, and suddenly the idea for a new book came out of nowhere.

“What if this girl wakes up one morning and finds that in the middle of the night her entire family has disappeared?”

By 8.30 a.m. he had e-mailed this idea to his agent. Within 10 minutes she was on the phone urging him to start work on the novel with- out delay. The result was his breakout novel, No Time To Say Goodbye, which went on to sell a million copies in the U.S. and Germany alone and made it possible for Linwood to become a full-time novelist.

“Suddenly there was a whole bunch of money . . . and The Star was offering buy-outs. It was an agonizing decision to quit, because I really loved doing the column. Because I’m very conservative financially, I was not prepared to leave until I could make multiples of my Star salary in books. But finally I decided it was time to move on to the third act.”

He has now produced eight crime thrillers since his breakout novel, and they occupy a prominent place in bookstores on both sides of the ocean. And members of his expanding cast of characters frequently show up in more than one book. No Safe House, published by Double- day in 2014, brings back characters we first met in his first success, No Time To Say Goodbye. After several years, Terry Archer and his family continue to be haunted by the horrifying experiences recounted in the previous novel. Now, they face new jeopardy when rebellious daughter Grace rashly follows her boyfriend into an unoccupied house and unleashes a terrifying chain of events in a community already jittery over serial killings.

Characters from the past again inhabit Linwood’s new novel, Bro- ken Promise, published in late July of this year. This is set in Linwood’s favourite fictional venue, the New York town of Promise Falls, and deals with a succession of bizarre events — the abandonment of an infant, the mysterious murder of the baby’s mother, the exposure of family secrets, and ritual slaughters of animals.

Linwood is trying something new with Broken Promise. It has a genuinely scary ending and is the first of a trilogy of thrillers featuring the same characters. “Let’s hope it isn’t a massive gamble, but everyone seems on board with it, so I’m excited,” he says.

His books continue to reflect his interest in troubled family dynamics, and he admits that it’s the teenagers who frequently trigger mayhem in his books. In the 2013 novel, A Tap At The Window, its hero makes the mistake of his life when he gives a lift to a teenaged female hitch- hiker.

“I think I certainly exaggerate the kind of mayhem teenagers can get into,” Linwood admits. But they often give him a conduit into stories that, for all their nail-biting tension, also help him explore a favourite theme — that of a beleaguered family struggling against destructive odds. “And anyway, I like to think that when I write about teenagers, I do see things from their point of view, and not just from the point of view of an exasperated parent.”

The Barclays’ son and daughter are now adults, but “they were pretty good kids. I think probably, as teenagers go, we got off easy.”

Both daughter, Paige, and son, Spencer, received a thank-you in an afterword to No Safe House. It’s Spencer’s film production company that produces the two-minute movies promoting each new novel on Linwood’s website. Paige assists with those and also helps her dad with his e-mails. Linwood is attentive to his fans and never takes them for granted.

“I think they’re 70 per cent women be- cause I think women read more fiction than men do. But I also receive e-mails from teenagers, the sort of thing that says, ‘I absolutely loved your book. I’ve been reading all this Twilight stuff, and my mom said I should read yours, and I loved it.”

And, says Linwood, “It’s kind of wonderful to get those sorts of letters from young readers.”

He considers himself the luckiest of people.

“The real pleasure, I guess, is being able to do what you like and to get paid for doing what you enjoy. It’s making up stories. It’s the fun that comes when you do something that you really think clicks, that really comes together. Plotting is the thing I work on the most because I want a good plot that’s believable, but also surprises and offers twists that are not just twists for the sake of twists, but make sense organically.

“And one of the big pleasures is being finished. That’s when I clean my desk and it be- comes spotless. But don’t worry — it will all get messed up again!”

–