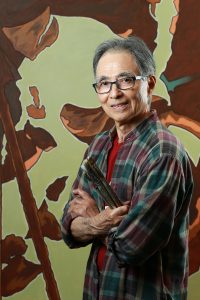

Famed artist and designer Norman Takeuchi bridges generations and cultures

By Paul Gessell

Photos by John Major

For much of his life, Ottawa artist and designer Norman Takeuchi rejected his Japanese-Canadian heritage. This was because of the “shame and humiliation” he felt ever since the Second World War when 22,000 British Columbians of Japanese ancestry, including Takeuchi’s family, were considered threats to national security, stripped of all their possessions and forcibly exiled from the west coast into the B.C. interior.

At age five, Norman was treated like a criminal as he, his parents and his two younger brothers, Bob and Ken, were forced to leave their Vancouver home. That

At age five, Norman was treated like a criminal as he, his parents and his two younger brothers, Bob and Ken, were forced to leave their Vancouver home. That

feeling of being “a second class citizen” remained for decades, even after Norman became a celebrated artist and sought-after designer, leaving his imprint on the

look of such iconic institutions as the Canada Pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal and on countless exhibitions at the Canadian Museum of Nature. Norman’s paintings, many referencing the wartime internment, are found in the permanent collections of such public institutions as the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, the Canadian War Museum and the Ottawa Art Gallery.

A turning point came in 1995, half-a-century after the war ended, when Norman saw an exhibition of “incredibly beautiful” kimonos by Japanese artist Itchiku Kubota at what was then called the Canadian Museum of Civilization. “If ever the phrase ‘timeless beauty’ had any meaning, it is here, ”art critic Alan King wrote about the kimonos in The Ottawa Citizen. Norman agreed. “I was so knocked-out by this and thought, ‘This is a Japanese person doing this kind of work. He is so revered in Japan for the work he did, he was considered a living treasure.’”

Norman’s attitude towards all things Japanese, including his own ancestry, slowly began to change. “It did make me think of who I am and my own ethnic background and that there are Japanese like Itchiku Kubota who can do these beautiful things. It made me feel quite proud. It didn’t affect my work right away,

but it did sit at the back of my head for several years. At some point, I started thinking about my heritage and maybe I should incorporate it into my work. I got tired

of thinking I am a second-class citizen and there are positive things about being Japanese and that I should consider that more seriously and give myself some self esteem.”

Kimonos became the medium for Norman to express his feelings and emotions. These garments are an iconic emblem of Japan. Rather than create actual cloth kimonos, Norman began painting images of kimonos on canvas. The paintings came to the attention of Ottawa art historian and curator Maureen Korp, who asked Norman to join a group exhibition on human rights issues called Without a Passport at the Karsh-Masson Gallery in 2006. He created a multimedia installation called A Measured Act — a play on the name of the law, the War Measures Act, that had exiled his family.

A Measured Act includes five life-sized paper kimonos that combine dark, abstract forms with photo transfers of historical images and documents related to the Japanese-Canadian internment. Alongside the kimonos are two wooden shelves containing crayon drawings of everyday objects — a teapot, a bowl with chopsticks, a small bottle of soy sauce — the exiles were allowed to take with them into internment camps, or in the case of the Takeuchi family, a succession of small towns where the parents were obliged to find menial jobs as lumberjacks and fruit pickers to put food on the table. “I consider that to be one of the key works of my career,” says Norman. Korp says A Measured Act is “as important a statement of truth” as

Picasso’s famed anti-war painting Guernica. That installation went on a Canadian and American tour after the Karsh-Masson exhibition and

has since been acquired by the Canadian War Museum. Laura Brandon, the museum’s former art curator, recommended the museum acquire the work. “It was accessible to our visitors as the stories were told on kimono shapes,” says Brandon. “I liked the fact the work referenced the past

militarily and culturally, while also speaking to contemporary audiences in its approach.”

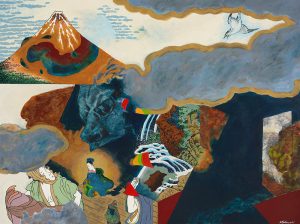

After A Measured Act, Norman changed directions in his painting. Instead of kimonos, he created semi-abstract scenes on canvas with large swaths of paint, often an angry-looking red, separating various Canadian and Japanese iconography that seem to be in turmoil. Lately, the style of those paintings has evolved. Tranquil blues often replace the angry red. Bucolic scenes of Canadian mountains appear alongside stereotypical images from ancient Japanese art. But there are still reminders of the internment. One unfinished painting recently seen in Norman’s west end studio, shows the filthy horse stalls in a barn in Vancouver’s Hastings Park, where many Japanese Canadians were forced to stay temporarily after being forcibly removed from their own homes.

After A Measured Act, Norman changed directions in his painting. Instead of kimonos, he created semi-abstract scenes on canvas with large swaths of paint, often an angry-looking red, separating various Canadian and Japanese iconography that seem to be in turmoil. Lately, the style of those paintings has evolved. Tranquil blues often replace the angry red. Bucolic scenes of Canadian mountains appear alongside stereotypical images from ancient Japanese art. But there are still reminders of the internment. One unfinished painting recently seen in Norman’s west end studio, shows the filthy horse stalls in a barn in Vancouver’s Hastings Park, where many Japanese Canadians were forced to stay temporarily after being forcibly removed from their own homes.

Large equilateral triangles thrust their way into many of the canvases. All sides are equal in these triangles, signifying harmony between the Japanese and Canadian aspects of the artist, who was born in Vancouver in 1937.“I have learned to embrace the two cultures, ”he says in a prepared, artist’s statement. Some of these new paintings will be in a planned exhibition this November at Norman’s Ottawa dealer, Studio Sixty Six, in Ottawa’s trendy Glebe area.

The evolution of Norman Takeuchi, the artist, began in childhood during the internment, when he drew pictures in such small B.C. towns

as Westwold, Devine and Robbins Range. The family returned to Vancouver in 1952. Norman’s father, Nawoki, re-established his gardening business

and his mother, Miyoko, opened a dress-making shop. They never discussed their wartime experiences with their three sons. Norman wishes now he had asked more questions, demanded more answers. But his parents were like returned soldiers, reluctant to revisit the trauma of the war.

As a teenager, Norman did not see art as a profession, although there was clearly an artist waiting to emerge. Prompted by his wife, Marion, he tells the story of being a teenager and working on a paint-by-number kit. He rebelled at the lines that he was supposed to respect separating colours. A true artist would “blend” one colour into the next. And Norman was a true artist.

After finishing high school in 1956, Norman decided to study architecture, a more secure profession than art. However, Norman complied with his father’s request to work with him in the gardening business for one year before attending university. In the evenings, Norman took night courses at the Vancouver School of Art. “As soon as I was in that building, I realized that’s where I belong, not in university. So, when I finished that year with my dad, I went to art school and enrolled.” During those years, Norman embraced abstract expressionism, a genre of spontaneous abstract art popular in the 1950s and practiced by such celebrated American artists as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Willem de Kooning.

Norman’s graduating class at the Vancouver School of Art in 1961, held an exhibition. A representative of the advertising firm Goodwin-Ellis attended the show, took a shine to Norman’s

paintings and immediately offered him a job. He accepted, but nine months later, Norman learned he had been awarded a grant from Vancouver’s Leon and Thea Koerner Foundation, enabling him to quit his job, move to London, England, set up a studio and paint for a year.

At the end of the year, Norman had an exhibition of his paintings, in London. Many of the works were semi-abstracts of birds. “The paintings were rather grim,” he recalls. “I felt quite lonely.” But he was delighted to learn some of the paintings sold. Back home in 1963, Norman met his future wife Marion in Ottawa at a party. They operate as partners in the art world. The following statement appears on the website of General Fine Craft, Norman’s dealer in Almonte, near Ottawa: “Norman is keenly aware that his art career would not have progressed as it has, if it wasn’t for the vital role Marion has played in providing support in countless ways: as organizer, archivist, bookkeeper, gentle critic; so much so, that it is impossible to not view the two as a team.”

At the end of the year, Norman had an exhibition of his paintings, in London. Many of the works were semi-abstracts of birds. “The paintings were rather grim,” he recalls. “I felt quite lonely.” But he was delighted to learn some of the paintings sold. Back home in 1963, Norman met his future wife Marion in Ottawa at a party. They operate as partners in the art world. The following statement appears on the website of General Fine Craft, Norman’s dealer in Almonte, near Ottawa: “Norman is keenly aware that his art career would not have progressed as it has, if it wasn’t for the vital role Marion has played in providing support in countless ways: as organizer, archivist, bookkeeper, gentle critic; so much so, that it is impossible to not view the two as a team.”

Also, in 1963, Norman was hired by the federal government’s exhibitions secretariat, initially to design displays at trade shows and later to design various elements of the interior and exterior of the Canada to return to London and paint. He never did visit Expo after it opened.

Norman and Marion both speak fondly of their year in London. They became fans of contemporary dance. They went to the ballet and saw Rudolf Nureyev perform. They attended many concerts. And Norman, of course, painted. But another stint as a designer awaited. Canada was preparing its pavilion for the world’s fair in Osaka, Japan in 1970. Norman was Pavilion at Expo 67.Norman was surprised and thrilled to see many photographs of his handiwork still circulate on the Internet.

Norman is proud of his Expo 67 accomplishments, but working conditions were not ideal. “When Expo opened, by then I was fed up with the job. As we got down to the wire, everything was going haywire. Everyone was snapping at each other. I had reached the point where I wanted to get out. On the day it opened, Marion and I were flying over the site to go to London. ”Norman had received a Canada Council grant to return to London and paint. He never did visit Expo after it opened.

Norman and Marion both speak fondly of their year in London. They became fans of contemporary dance. They went to the ballet and saw Rudolf Nureyev perform. They attended many concerts. And Norman, of course, painted. But another stint as a designer awaited. Canada was preparing its pavilion for the world’s fair in Osaka, Japan in 1970. Norman was offered a job in 1968 to work on the project. That involved living in Japan for six months installing exhibitions. It was Norman’s first trip to the country of his ancestors.

“It was awkward, ”Norman says of his Japanese stay. He looked Japanese and everyone assumed he could read and write the language. But he knew only rudimentary Japanese, certainly not enough to fill out a hotel registration card. (Marion, who speaks some Japanese, compares her husband’s fluency in the spoken language at the time to that of a four-year-old.) “In terms of appearance, I fitted in, but I felt like a stranger because of where I am from and I felt like I was in a foreign land looking at some really exotic looking people.”

“It was awkward, ”Norman says of his Japanese stay. He looked Japanese and everyone assumed he could read and write the language. But he knew only rudimentary Japanese, certainly not enough to fill out a hotel registration card. (Marion, who speaks some Japanese, compares her husband’s fluency in the spoken language at the time to that of a four-year-old.) “In terms of appearance, I fitted in, but I felt like a stranger because of where I am from and I felt like I was in a foreign land looking at some really exotic looking people.”

And then there were the Japanese workmen on the Osaka 70 site. They swaggered as they walked and had wide, two-sided saws hanging from their belts. To Norman, they looked like Samurai warriors. He felt “inferior and intimidated.” He also felt a lot more Canadian. “I certainly felt like a foreigner.” So did Norman’s parents, who came for a visit. His father was born in Japan but not his mother. They both spoke Japanese, but were reluctant to do so, believing their vocabulary was old-fashioned.

After Osaka, Norman was hired as a designer by the Canadian Museum of Nature, shaping the look of exhibitions on everything from muskoxen to polar bears and bats. He worked there from 1970 to 1996. During that period Norman had a near fatal health episode from a bleeding ulcer. He changed his diet, painted “only sporadically” for several years and started bicycling to become more physically fit. Just a few years ago, he started curling regularly. Now in his 80s, he remains slim and trim.

In 1996, Norman took early retirement from the nature museum so he could devote himself full-time to his art. It was the beginning of a second career, at age 59. He threw himself completely into painting and exhibiting his work in galleries across Canada.

One exhibition at the now-closed Cube Gallery, in 2010,had a lasting impact on Norman and on Frances Itani, the Ottawa-based author of such celebrated novels as Deafening and Tell. Itani was completing her novel, Requiem, about a Japanese-Canadian artist, Bin, who had been interned during the Second World War and had never really come to terms with his traumatic past. Itani read a Citizen article about Norman’s Cube Gallery show and decided to meet the artist.

“I thought, well, this is the man for me,”Itani recalls in an email interview. “I’ll have to meet this artist, because he’d be about the age of my character in Requiem. Itani went to Cube, met Norman, and interviewed him several times.

“Many of the ‘studio’ details in Requiem are from Norman’s actual work environment,” says Itani. “We met at his home, and several times after that in restaurants or for coffee, and I always had my notebook at hand, and threw questions at him. He was very generous with his time and knowledge. For me, learning about the art materials, the studio practices, etc., were really helpful to my book.” Itani, and her Japanese-Canadian husband Tetsuo (Ted) became fast friends with the Takeuchis.

Read the book to discover what Bin decided. We can, however, say that Norman Takeuchi has made a peace — of sorts — with his ghosts. He now takes pride in his heritage. The anger over internment has not vanished, but it does not consume him. Instead, it is channelled into a successful career as an artist.

Norman Takeuchi’s exhibition “Equal Time”

November 13 to December 23, 2020

Studio Sixty Six, 858 Bank Street, Ottawa